Wealth has been getting a lot of attention in Ireland recently particularly in relation to the claim that it would be possible to raise €10 billion per annum from a 5% wealth tax on the wealthiest 5% of the population as detailed in the Budget Submission of the United Left Alliance and repeated on an almost nightly basis on television and radio.

The adult population of Ireland is around 3,400,000 so the 5% that are liable for this tax would be 170,000 people. In order for the €10 billion total to be achieved these people would have to be pay an average of an additional €60,000 in tax every year.

The ULA’s budget submission also envisages an additional €5 billion of income tax to be raised from those earning in excess of €100,000. According to data from the Revenue Commissioners in 2009 there were 110,000 tax cases reporting an income in excess of €100,000. The average income in this category is €180,000, but two-thirds of those who earned more than €100,000 earned less than €150,000. In order for the €5 billion target to be achieved those earning more than €100,000 will be required to pay an average of an additional €45,000 of income tax.

This is an addition to the €60,000 average income tax that this group paid. In 2009, this excludes payments made because of the Health Levy and also PRSI contributions. Anyway, the focus here is on the potential to raise €10 billion from a wealth tax.

Back in February the United Left Alliance were proposing that €6 billion a year could be raised from a wealth tax. Just ten months later they have increased this to €10 billion.

The original claims were based on a 2006 report by Bank of Ireland Asset Management on The Wealth of The Nation. The current claims are based on the Global Wealth Report (and accompanying Databook which has the details on Ireland) from Credit Suisse. For 2011, the report estimates that the average net wealth per adult in Ireland is $181,434 (median equals $100,351). With an adult population figure in the report of 3,403,000 that puts total net wealth in Ireland at $617 billion.

The Credit Suisse report estimates that there are around 70,000 millionaires in Ireland (and four billionaires). This means that around 100,000 of those in the top 5% have a net wealth of less than €1 million. Net wealth is

Financial wealth + Non-financial wealth - Debts = Net wealth

This figures under each heading are:

- Financial wealth $435 billion

- Non-financial wealth $484 billion

- Debt $302 billion

We are not given an exchange rate to convert this into € but the euro has recently been around 1.30 to the dollar but was probably trading higher when this report was written. If we use an exchange rate of €1 = $1.40 that would give:

€310 billion + €345 billion - €215 billion = €440 billion

The estimate is that there is €655 billion of gross assets in Ireland and €440 billion of net wealth. The 2006 figures from the earlier Bank of Ireland report are:

€270 billion + €695 billion - €161 billion = €804 billion

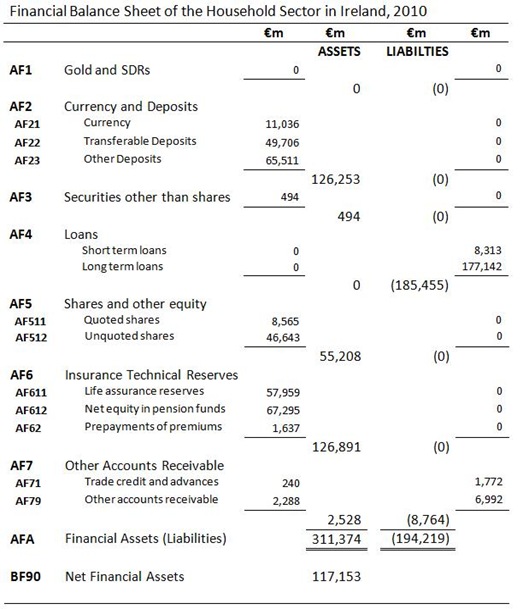

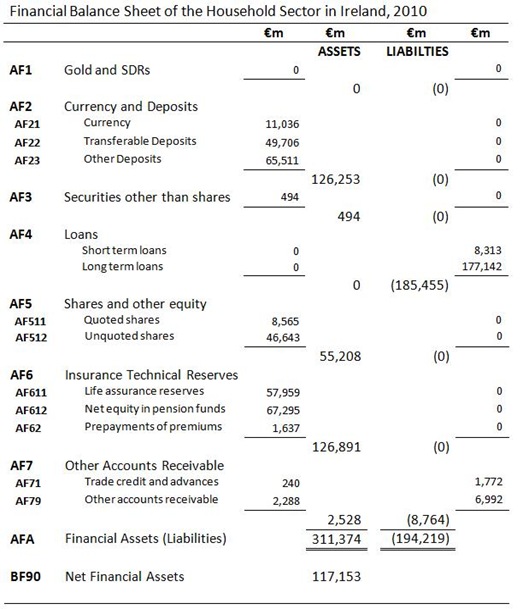

The figures provided by Credit Suisse for financial wealth and debt are not that distant from the official figures given in the CSO’s Institutional Sector Accounts. This puts financial assets of the household sector in Ireland for 2010 at €311 billion and household financial liabilities at €194 billion. The asset figure is almost identical to the Credit Suisse figure but the liability figure is a little higher than the CSO’s.

The CSO put total financial wealth in the household sector at €117 billion. The following gives the breakdown of the assets and liabilities that gives rise to this figure.

The Bank of Ireland report puts the 2006 total of financial assets at €270 billion and exclude life assurance reserves from their total. Credit Suisse have a figure of €310 billion but the composition of this is not given.

To get a measure of overall wealth we need to add non-financial assets to those listed above. The Bank of Ireland report includes residential (€671 billion) and commercial (€24 billion) real estate in the €695 billion total for 2006 in that report, but seem to exclude land and other assets. Even putting an approximate value on all of these assets is extremely difficult.

It is not clear what Credit Suisse include as non-financial wealth but is it “principally housing and land” and they provide a figure of €345 billion but there is no way of knowing how this is derived.

The CSO do not provide an estimate of non-financial wealth in Ireland but the organisation’s Action Plan under the Croke Park Agreement states that “there is demand for a … survey

of household Income, Wealth and Assets.” It is not clear when this will be delivered.

And finally onto the distribution. Credit Suisse estimate that 5% of adults (175,000) have 46.8% of the €440 billion of the net wealth they estimate that is in the country. This is equal to €206 billion and would be an average of around €1.17 million per person.

A division of this by financial and non-financial assets is not provided and it is unclear what the asset allocation across this €206 billion is. Apart from the nebulous concept of “wealth” in the ULA document it is not clear what should be taxed. It will take a little more than an amendment to the Finance Act proposing that “a 5% tax be imposed on the wealth of the wealthiest 5% of the population”.

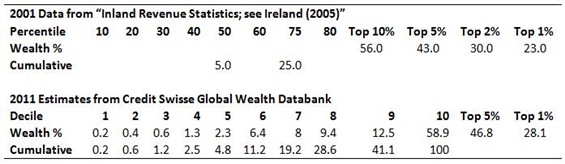

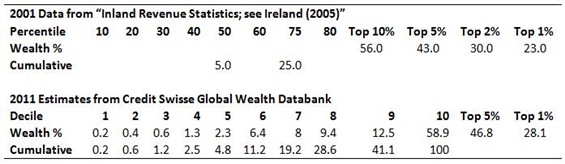

It is also not clear how sound this wealth distribution is. The Credit Suisse report says that it has wealth distribution data for 22 countries and uses this data to infer distributions for the other 140 countries in the report. Ireland is one of the countries that they claim to have wealth distribution data for and this is from 2001. The 2001 data and the 2011 estimates are summarised in the following table.

The series are reasonably consistent. The 2001 figure is that the bottom 50% have 5.0% of the wealth. For 2011 the reported figure is 4.8%. In 2001 it is indicated that the top 10% has 56% of the wealth, in 2011 it is 58.9%. For the top 1% the figures are 23.0% and 28.1%.

But where did the 2001 data come from? The report says the data is from Inland Revenue Statistics and to go see Ireland (2005). I doubt the UK’s Inland Revenue have data on the distribution of wealth in Ireland and we know that the Revenue Commissioners do not. The Inland Revenue may have data on Northern Ireland and they have lots of neat stuff here.

So what is this reference to Ireland (2005). From the bibliography this is:

Ireland, P. (2005): “Shareholder Primacy and the Distribution of Wealth”, Modern Law Review, 68: 49-81.

You can read this article here but the only mention of Ireland is because of the name of the author – Paddy Ireland. There are no wealth distribution statistics for Ireland in the article. None, but the reference has the words “Ireland”, “wealth” and “distribution” in it!

This report by the some of the same authors has almost the same wealth distribution as those shown in the top of the above table. The only issue is that there are for the UK in the year 2000. See table 7 on page 37.

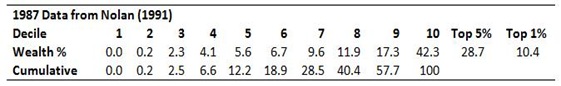

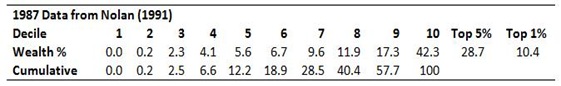

There is another wealth distribution provided for Ireland in this report but this is claimed to be from 1987 and cites a 1991 publication by Brian Nolan, The Survey of Income Distribution, Poverty and Usage of State Services. However I think they actually a 1991 publication for the Combat Poverty Agency, The Wealth of Irish Households: What Can We Learn from Survey Data? (32mb!). Anyway here is the 1987 data which is confirmed on page 69 of the Combat Poverty Agency report.

When using the 1987 data this earlier report says “it is hoped that the shape of wealth distribution in these countries was reasonably stable from the late 1980s to the year 2000”. By 2001, in the Credit Swisse report they are saying that the wealth share of the top 1% was 23.0% up from 10.4% in the 1987 data. Not very stable. Of course, this 23.0% is a UK figure so we cannot put much weight on it.

In fact, without any evidence to support the claims in the report we cannot put any weight on it at all. Hopefully in time the CSO will address this data deficiency. The Nolan (1991) data is from a survey which will tend to underestimate the wealth of high and very high net worth individuals as they will be under-represented in the sample. Any information on the 2011 distribution of wealth in Ireland is little more than a guess.

A 5% tax on €206 billion would yield an impressive €10.3 billion but the proposal must specify what is to be taxed. The possibilities are:

- Cash

- Current Accounts and Deposits

- Life Assurance Reserves

- Direct Equity Investment

- Business Equity

- Pension Fund Equity

- Land

- Commercial Property

- Residential Property

- Other Assets

Putting a 5% tax on cash, current accounts, bank deposits and life assurance reserves seems practically impossible. The value of equities or private business comes from the dividends or incomes that these assets can generate and this are taxed under the income tax code. We have introduced a 0.6% annual pension levy for private pensions. A land tax is possible but unlikely and a residential property tax (or more particularly a site value tax) is due to be introduced by 2014. Determining what other assets should even be included makes taxing them difficult (yachts, racehorses, art, antiques, cars, jewellery, …)

All this is not to say that a wealth tax does not have merits. There have been moves away from wealth taxes in the past 15 years with many European countries abandoning them but France maintains the ‘Solidarity Tax on Wealth’. This is liable on net assets above €800,000 and was paid by 1% of taxpayers in 2007. See here and here for details (thanks to the Wikipedia entry) with more here and here.

The tax raises about 1.5% of general government revenue in France and is at a rate of around 0.5% of taxable net assets for the majority of those who pay. The ULA proposal seems to be to set these at a level ten times larger in Ireland – t0 raise 15% of revenue at a rate of 5% of net assets – and to levy it on five times as many people.

There is no way that this can be realistically achieved. The numbers on which the claim is based are questionable but to push the proposal to such drastic lengths is absurd. If we got €1 billion from a wealth tax it would be a start.

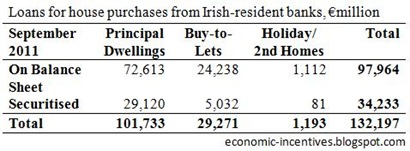

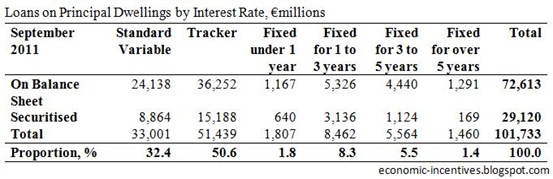

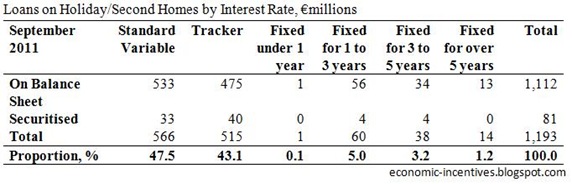

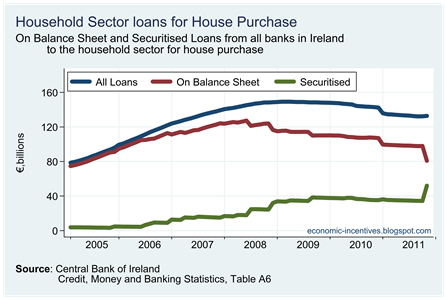

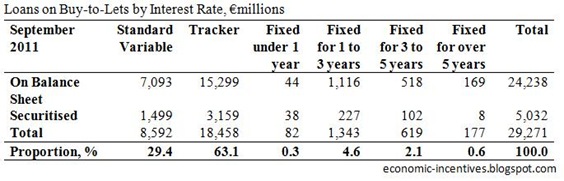

Although they make up a very minor part of the overall market here is the same data for holiday home and second home mortgages.

Although they make up a very minor part of the overall market here is the same data for holiday home and second home mortgages.