There has been a lot of discussion following from Michael Noonan’s comments last week that “what we really need is for people to go into the shops and start buying again”. Stephen Kinsella has a good post on this. As a follow up to this it is useful to consider just what it is Irish people are saving. To start here is a highly stylised and artificial example.

Consider that society is made up of two groups and that the disposable income of each group is 50. The first group is the Thrifty Group. Of their disposable income they spend 40 and save 10. The second group is the Profligate Group. They spend their income of 50and also borrow an additional 10 to increase their consumption to 60.

In this first period aggregate disposable income is 100 and total consumption is 100. The savings rate is zero.

We then move to the second period. The situation and behaviour of the Thrifty Group does not change. They continue to have a disposable income of 50, spending 40 and saving 10 of this. We will also assume that the disposable income of the Profligate Group does not change but they are now unwilling/unable to borrow to fund their consumption and they spend their entire disposable income of 50.

In this second period aggregate disposable income is 100 and total consumption is 90. The savings rate is 10% but this was driven by a change in borrowing behaviour. There has been no change in savings behaviour.

Finally, consider a third period. Again we will assume no change for the Thrifty Group but now the Profligate Group have to pay back the money they borrowed in Period One. We will assume that this requires a repayment of five, thus reducing their consumption to 45.

In this third period aggregate disposable income is 100 and total consumption is 85. The savings rate is now 15% but again it is not because of any increase savings behaviour.

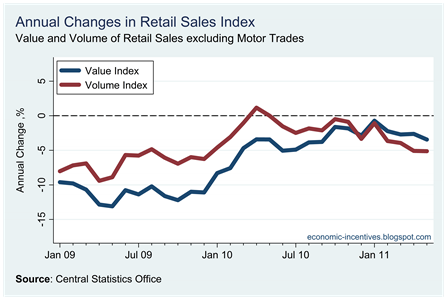

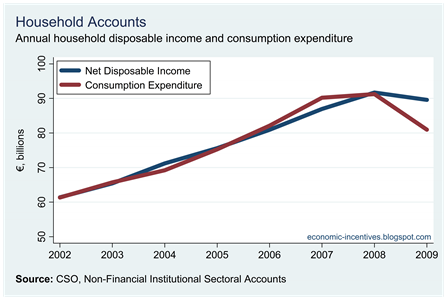

In Ireland the savings rate has shot up in recent years.

The suggestion from Michael Noonan is because this is as a result of an increase in savings behaviour. It is true that a gap has emerged between household disposable income and household consumption.

Although the data in this graph only go to 2009 all indications are that this continued into 2010 and will likely continue in 2011 and 2012. In economics, the definition of savings is disposable income that is not spent.

In 2008, both disposable income and consumption expenditure were around €90 - €92 billion. In 2009, household disposable income fell slightly but consumption expenditure dropped from €90 billion to €81 billion. The assumption is that this €9 billion is money that households could have spent, but are now choosing to save. As we saw with our stylised example above, this could be a factor of borrowing rather than saving.

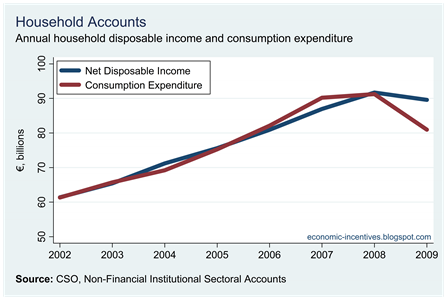

If we look at household financial accounts we see that this is more than likely the case. First here are household deposits.

During 2006 to 2008 when the savings rate was low household deposits were rising. When the savings rate shot up in 2009, the increase in deposits slowed and had even begun to decline slightly during the end of 2010. This is an aggregate of deposits. It is likely for some households that precautionary deposits are increasing while for other households deposits are decreasing as they use them to offset significant reductions in income.

The savings rate might be a hefty 12% but this is not been seen in household deposits. Michael Noonan may want people to go out shopping but they do not have an extra savings to draw on, household deposits are falling.

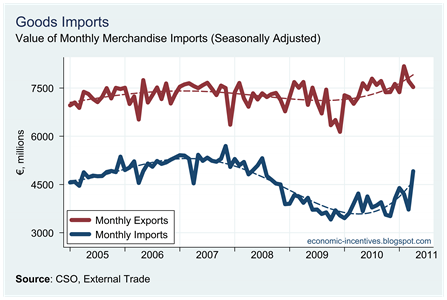

So where is the 12% savings rate going? Well, as explained above it could be driven by a fall in new borrowings. The Credit, Money and Banking Statistics from the Central Bank show that household credit is now contracting.

The drop in growth of consumer credit is evident and since 2008 has moved from growing at 18% per annum to falling at 18% per annum. Even if household income and savings amounts had remained unchanged this huge turnaround in consumer credit would have seen consumption expenditure fall.

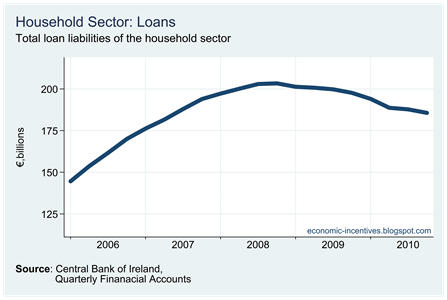

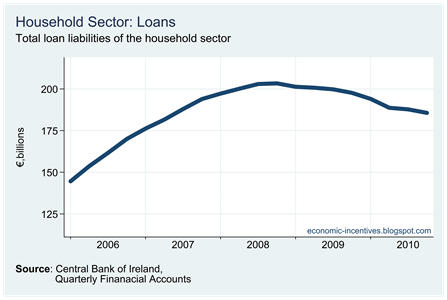

Finally here is the aggregate amount of loans owed by households.

Since peaking in the middle of 2008, the amount owed on household loans has fallen from €203 billion to €185 billion. Short-term loans have fallen from €14 billion to €9 billion.

The household sector may have a savings rate of close to 12% but there are no swelling deposits that could be used to boost consumption. The savings rate has shot up for two reasons:

- Households are no longer borrowing to fund their consumption expenditure.

- Households are paying back the loans they previously used to fund their consumption expenditure.

One issue that cannot be addressed here is whether people are paying back these loans in an accelerated fashion. The Financial Regulator produces data on mortgage arrears, those behind on their repayments. It would be useful if we could get even a snapshot of those who are in mortgage advances, those ahead on their repayments.

There may be households who are saving by paying down loans quicker than in the original contract. It is difficult to say if this is true but the total amount of loans outstanding to households is falling quite rapidly. It must be stated that it is falling from a huge height and is still 120% of GDP, well north of international averages.

So what impact is this huge savings rate having on household deposits? Very little. What extra money is available for consumption? Not much. There may be some money that is currently being used to accelerate the repayment of debt. This will continue for the medium term and once households have repaired their balance sheets they will be in a position to increase consumption relatively quickly. It will take more than words from the Minister for Finance to get the tills rolling again.