It has been a confusing day for reports on the savings behaviour of Irish households. One story on the Irish Times site tells us that:

The savings index fell from 98 to 81 in December, the lowest ever level since the index's inception in April 2010, as increased negative sentiment towards the economic environment discouraged saving.

While another story posted to the same site says:

The institutional sector accounts, which brings together information on the activities of households, businesses and the Government, show that the gross amount of household savings was €11.92 billion for the first three quarters of 2012. This is more than the €9.3 billion of total savings recorded during 2011.

The derived gross savings ratio increased by 14.5 per cent in the second quarter to 16 per cent in the third quarter last year. This ratio expresses household savings as a percentage of gross disposable household income.

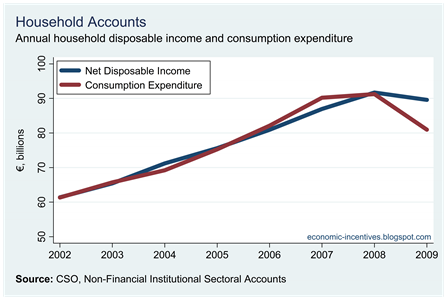

Of course, the Savings Index from Nationwide UK (Ireland) and the Institutional Sector Accounts from the Central Statistics Office are dealing with very different meanings of the term ‘saving’. The focus here is on the measure produced by the CSO which relates to the gap between disposable income and consumption expenditure and is shown in the following chart. The savings rate is the percentage of gross disposable income (plus an adjustment for pension funds) that is not spent on consumption.

It is often suggested that the current rate is somehow “too high”. A recent Irish Examiner report states that:

At a press briefing to announce the end-of-year exchequer figures on Thursday, Finance Minister Michael Noonan said that the national savings rate was now 14%, compared with 1.5% during the Celtic Tiger years. If people spent more and brought the savings rate down to 10%, then it would add 1% to growth, the minister said.

Is Ireland’s savings rate “too high”? The Q2 2012 figure shown in the above chart is 14.5%. Eurostat figures show that the EZ17 figure for the same quarter was 12.9%. In fact, after going above the EZ17 rate for the first time in Q1 2009 the Irish savings rate was below the EZ17 average for the next three years. It is only in Q2 2012 that the rate has exceeded the EZ17 average.

While the Irish household savings rate has shown some volatility over the past decade, the most dramatic changes in household behaviour have not been to do with savings but to do with capital formation (investment in non-financial assets). In national accounts, household investment mainly consists of the purchase of new dwellings and the renovation of existing dwellings.

Household investment has gone from close to 30% of gross household disposable income in 2006 to less than 5% now. Again the comparison to the EZ17 average is revealing.

Compared to the EZ17 average, the household investment rate in Ireland has gone from being significantly “too high”, to what seems to be a small bit “too low”. The household investment rate fell dramatically from 2007-2009 and has continued to fall, albeit more slowly, since then. By Q3 2012, the household investment rate in Ireland had dropped to a low of 3.6% of gross disposable income. The EZ17 average is around 9%.

The gross investment rate of households is defined as gross fixed capital formation divided by gross disposable income, with the latter being adjusted for the change in the net equity of households in pension funds reserves.

In the first three quarters of 2006, the household sector in Ireland invested €19.5 billion in gross capital formation in non-financial assets (mainly buying new houses but also paying stamp duty on second-hand houses). For the first three quarters of 2012, the equivalent figure is €3.8 billion, a drop of more than 80% from the peak.

If the EZ17 average of a 9% household investment rate applied in Ireland then the 2012 figure for the first three quarters would be €6.2 billion. The quote from Michael Noonan above shows that he thinks that reducing the savings rate to 10% (below the EZ17 average) would add 1% to GDP growth. However, if the household investment rate rose to 9% (just equal to the EZ average) it would add 2% to GDP growth.

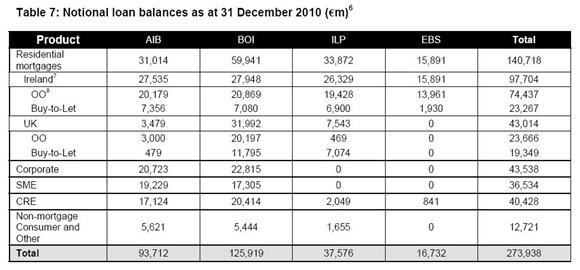

Where is this saving going? Excluding the adjustment for pension funds the household sector “saved” €31 billion in the two and a half years from the start of 2009. As it wasn’t used to fund consumption where did this €31 billion go?

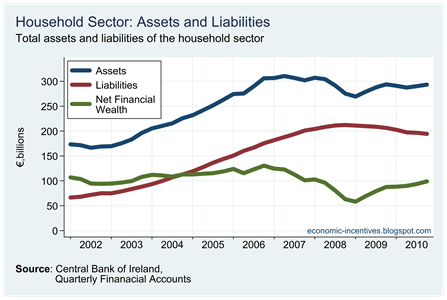

The Central Bank produces quarterly financial accounts which show the changes in the financial position of the household sector. For the household sector, the key measures are currency and deposit assets and loan liabilities.

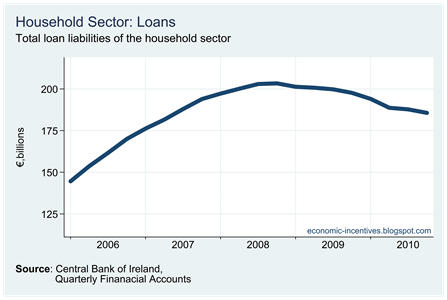

Since the end of 2008 the currency and deposit asset of the Irish household sector has hardly moved. It was €120 billion in Q4 2008 and was €124 billion in Q2 2012. Over the same period the loan liabilities of the household sector declined from €204 billion to €180 billion.

Since 2009, Irish households have not used €31 billion of their disposable income to fund consumption expenditure. In the main this unspent money has been used to pay down debt rather than accumulate deposits. The Nationwide UK (Ireland) survey shows that Irish households are not building up “savings”; the CSO data clearly show that Irish households are “saving” but that this is going to pay down debt.

The Irish background data used above in the non-financial charts and some additional comments are below the fold.

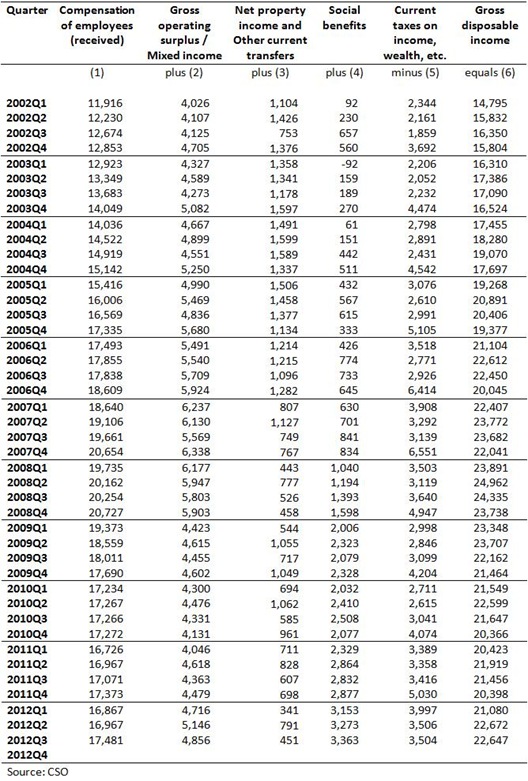

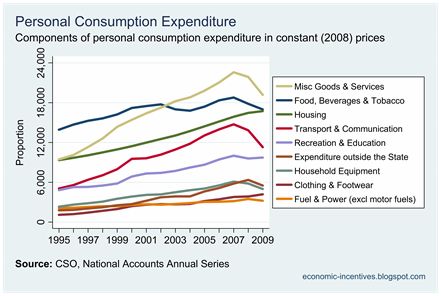

First, the components of Gross Household Disposable Income which is the sum of wages, self employed earnings/mixed income, property income and social transfers less taxes on income and wealth. Click to enlarge.For the first three quarters of 2012, gross household disposable income was €66.4 billion, which is a 4.1% increase on the €63.8 billion recorded for 2011. This increase in income is not reflected in household consumption expenditure which continues to flat-line.

The factors giving rise to the increase in gross disposable income are in the following table (all in €millions).

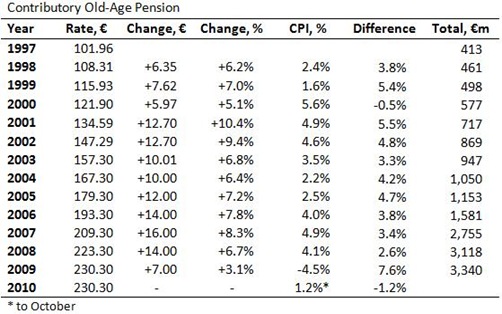

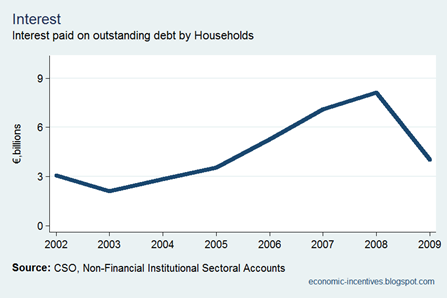

Wages received, non-wage earnings and mixed income, and social benefits all contributed to the increase in gross disposable income over the year. Offsetting factors were the reduction in net property income (mainly interest) and the increase in taxes on income and wealth.

Compared to the peak in 2008, gross household disposable income has fallen 9.3%. Over the same period there has been an estimated 2.2% increase in the population (4,485,100 to 4,585,400) so the fall in per capita income is even greater.

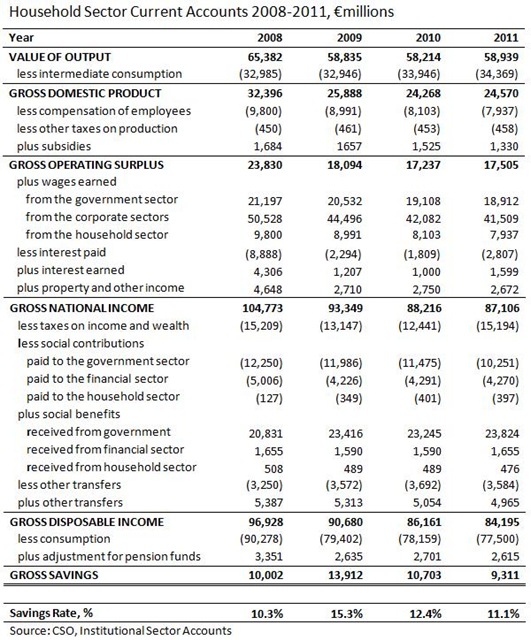

And here are the consumption, savings and investment figures. The savings and investment rates in the final two columns are four-quarter moving-averages. Click to enlarge.

Although the first table shows some positive signs with the recent rise in gross household disposable income there aren’t even hints of so-called green shoots from the household sector in the data in the second table – consumption expenditure is moribund and household investment continues to fall.

There were anecdotal claims that retail sales during the Christmas period and January sales were ahead of expectations. As “the plural of anecdote is not data” we will wait until the final column in the above table is filled in before drawing actual conclusions.