Here is an exchange from last week’s meeting of the Joint Committee on Finance, Public Expenditure and Reform Debate which was attended by members of the Independent Fiscal Advisory Council.

Deputy Mary Lou McDonald: Far from viewing Professor McHale as cautious or conservative, my reaction to his contention that the austerity should be greater and quicker is that it is reckless. I would like him to give us the rationale for his commitment to austerity. Where is the evidence it is working? We have not seen a dramatic reduction in the underlying deficit despite €20 billion having been sucked out of the economy.

Professor John McHale: Deputy McDonald asked if the austerity is working. By that I understand her to mean if it is succeeding in bringing down the deficit. The question is sometimes asked whether attempts at deficit reduction is self-defeating in that the deficit does not come down. In my view it is working. Our assessment of the numbers is that it is working. The overall general government deficit fell from 11.7% of GDP in 2009, and the most recent projection is that it will be 10.3% of GDP for this year, so that is a reduction. The Exchequer deficit for the first ten months-----

Deputy Mary Lou McDonald: Is that a satisfactory rate of decrease?

Professor John McHale: That is a good question. It looks like the Exchequer deficit for the first ten months of this year will be €1.8 billion lower than it was for the first ten months of last year.

In making an assessment, we have to recognise that austerity is not the only factor slowing down the economy. There are significant forces pushing the Irish economy down and this refers to the earlier discussion of the balance sheet recession. There are significant issues of confidence and issues of credit access. This economy has been hit with a number of very severe shocks that have been slowing growth and particularly slowing the growth of domestic demand, which is critical to the fiscal position.

The Deputy is correct that these numbers as regards improvement in the deficit are not startling in the sense that the deficit is on this incredibly slow downward path but the fact that this has been achieved in the face of such headwinds shows that it is actually working. It is hopefully a question of when we get back to growth and the measures taken, such as the new tax and expenditure structures, will yield much more. When we get back to growth and, particularly and crucially, growth in domestic demand which is affected by much more than just the austerity measures themselves, the expectation and the hope is that the deficit will improve more rapidly.

Using our fiscal feedback model, we have also conducted simulations of what would have happened if there had been no adjustment at all. The Deputy referred to the €21 billion adjustment which has taken place so far. On conservative assumptions, the deficit in 2011 would have been 20% of GDP instead of the projected 10.3% if there had been no measures taken. We would be heading for a debt to GDP ratio in 2014 to 2015 of approximately 180% of GDP. We would be fast becoming like Greece. We would probably never get there because we would probably have ended up in default before then.

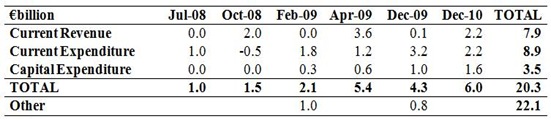

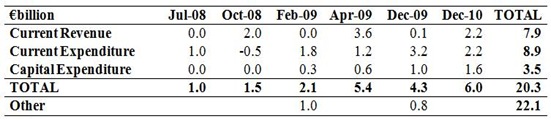

The question here is not so much on whether austerity is working but on what exactly entails the “€21 billion adjustment” which is referred to in the exchange. The McCarthy Report on State Assets provides a useful summary of the measures that have been introduced up to this year.

The sum of measure introduced is indeed €21 billion, but has €21 billion been “sucked out of the economy” over the last three years? The €21 billion was the projected full-year impact of the measures introduced. Maybe we should look at what actually happened to see how close reality is to this €21 billion. I think the answer is closer to €10 billion than it is to €20 billion.

To start we will look at what was introduced each time. First up is the €1 billion of measures introduced in July 2008. Here is the list from the Minister’s statement.

- All Departments, State Agencies and Local Authorities – other than Health and Education - will be required to reduce their payroll bill by 3% by the end of 2009 through all appropriate measures identified by local management in the light of local circumstances. The parameters of this exception for the health and education sector are to be agreed by the Departments concerned with the Department of Finance.

- All expenditure by Departments and Agencies on Consultancies, Advertising and Public Relations will be significantly reduced for the remainder of this year and by at least 50% in 2009.

- Further savings in 2008 and in 2009 are to be secured by a range of measures including those identified as a result of the Budget day efficiency review initiated by my predecessor.

- All of the above efficiencies will apply equally to State Agencies. In addition, I have asked that these agencies be reviewed to examine whether they can share services, whether it would be appropriate to absorb some of their functions back into their parent Departments or whether some agencies should be amalgamated or abolished. The outcome of this will be considered by the Government in the Autumn.

- The Government has also decided, in the light of the current Exchequer position, that further expenditure for the acquisition of accommodation for decentralisation will await detailed consideration of reports from the Decentralisation Implementation Group.

- Minister of State Martin Mansergh will head up a joint public procurement operation between OPW and the Department of Finance to drive a programme of reform and to produce a business plan for purchasing savings to be achieved by Departments and other public bodies in 2009. Minister Mansergh will report to me in the Autumn with specific proposals to target at least €50m savings in 2009 on this front.

- Given the projected revision to GNP and other factors, there will be savings in Overseas Development Assistance of some €45 million this year. The revised total contribution in 2008 will be over €200 per citizen, totalling around €900 million. Ireland will still be far ahead of almost all other developed nations in our rate of ODA.

It is hard to class much of these as anything at all. There are no tax increases and the expenditure measures are aspiration rather than actual.

The only actual cut was €45 million off the ODA budget. Outside of Health and Education the pay bill increased from €4.1 billion to €4.3 billion between 2007 and 2008. I don’t know what effect the announced cut in “Consultancies, Advertising and Public Relations” or “the Budget day efficiency review” had. Very little I would guess. This is €1 billion of the €21 billion but I don’t think it resulted in much austerity.

Lets move to October 2008 and the early introduction of Budget 2009. This was supposed to have revenue raising measures that brought in an extra €2 billion. What also seems to be missed is that this budget also had adjustments that INCREASED expenditure. The announced changes to social welfare in Budget 2009 had a full year cost of over €0.5 billion.

Fully a quarter of the money that was planned to be raised from extra taxation was spent before the Minister sat down. This isn’t “sucking money out of the economy”.

In the Budget speech the Minister also told us what happened to the savings made from the measures introduce the previous July:

The savings achieved have already been used to relieve pressures in areas such as:

-

health, where additional provision had to be set aside to meet the costs of a new consultants’ contract and

-

education, where the full year salary costs of about two thousand extra teachers and Special Needs Assistants taken on this year had to be provided.

The “savings” weren’t taken out of the economy; they were spent in the economy. And what about the €2 billion of revenue measures introduced? This table provides the full-year revenue effects from the Summary of Budget Measures document.

These do indeed total €2 billion. Of course the VAT increase to 21.5% was reversed in the following year’s budget so that €227 million was only temporary.

Although details of DIRT are not provided I would be pretty sure that the increase from 25% to 27% didn’t bring in an extra €85 million. When the Budget was announced on the 14th of October 2008 the ECB base rate was 4.25%, just six months later it was 1.25%.

The Budget estimate was that Capital Gains Tax in 2009 would bring in €1,700 million. What was the actual outturn for 2009? €542 million. It should be fairly evident that increasing CGT from 20% to 22% did not bring in an extra €160 million. Increasing the rate to 25% in the middle of the year was also ineffectual.

We can do the same for Excise Duty. Here is how the €491 million extra was supposed to be raised.

In 2008, Excise Duty brought in €5.60 billion. The Budget forecast for 2009 was €5.74 billion. Instead of rising by €150 million in 2009, excise duty revenue fell €700 million. Consumption of petrol fell 8.4%, consumption of cigarettes fell 6.7%, consumption of wine fell 6.9%, the betting levy wasn’t increased to 2% and the Air Travel Tax brought in €105 million in its first full year in 2010 and was never applied to “small peripheral airports”.

We’ll come back to the Income Levy but it is clear that the taxation measures introduced did not raise the planned extra €2 billion. Social welfare measures with extra expenditure of €0.5 billion were introduced. In the Budget net current expenditure for 2009 was forecast to be €48 billion. Net current expenditure in 2008 was €45 billion. And this is a budget that “sucked money out of the economy”?

Next up is the €2.1 billion of expenditure measures announced just four months later in February 2009. These measures are summarised in this table. Of the €1.4 billion to be cut from Public Sector Pay, €1 billion was to be raised by the Pension Levy. In its first full year in 2010 this returned €916 million, about 9% below the projection. (Can anybody guess why?).

It is not exactly clear where the other €0.4 billion of savings from Public Sector Pay were supposed to come from or whether they were achieved. There was also supposed to €140 million of “general administrative reductions”.

We just have to move forward just two months to the April 2009 Supplemental Budget which has €5.4 billion of revenue and expenditure measures. There was €3.6 billion of tax measures, with €2.8 billion to come from Income Tax changes. Unfortunately at the time we did not get an individual breakdown of what impact the doubling of the Income Levy, the Health Levy and the increase in the PRSI ceiling would have. We can use some other forecasts though.

In December it was revealed that when the rates were increased it was believed that the Income Levy would yield “approximately €2 billion in a full year”. In 2010, the first full year of the new rates the Income Levy raised €1,446 million – over half a billion lower than forecast.

In September it was revealed that the 2010 estimate for the Health Levy was €2,489 million which we can assume was close to the forecast used in April. The actual outturn for 2010 was €2,018 million – nearly half a billion lower than forecast.

I think we can take it that the change in the PRSI ceiling did not bring in as much as was forecast. It was announced that €2.8 billion of Income Tax measures were being introduced. The actual impact of them was much lower. The was nearly €160 million of capital tax measures announced and another €150 million excise duty measures which likely suffered a similar fate.

At the time of the 2009 Budget the previous October the estimate was that gross current expenditure would be €61,782 million in 2009. The actual outturn of gross current expenditure for 2009 was €60,711 million – a reduction of €1,071 million.

The February package included €790 million of full-year cuts in gross current expenditure. The 2009 savings would be slightly lower, lets say €600 million. The Supplemental Budget in April also included €886 million of cuts to gross current expenditure for 2009 (€1,215 over a full year). Combined these €1,486 million of cuts saw expenditure come in €1,071 lower.

Again it is hard to pin down where the failure arose. The expenditure measures were not very specific apart from axing the Christmas bonus payment for social welfare recipients (€171 million), yet another reduction in the overseas development aid budget (€100 million) and the abolition of the Early Childcare Supplement (€105 million) . There was €82 million to be saved in Social Welfare from “general control measures” and €150 million of payroll savings from a “range of initiatives”.

The Supplemental Budget announced that the 2009 capital programme would be reduced by €576 million on top of the €300 million announced in February. This was delivered on. The Budget estimate was that gross capital expenditure would be €8,231 million. The outturn was €7,329 million - a reduction of €902 billion. There seems to have been an abject failure to reach the levels announced for the measured announced in the current budget, but this appears to have been different in the capital budget.

Next up was the €4.3 billion of expenditure cuts and tax increases announced in Budget 2010. There was €0.1 billion of tax measures and, €3.1 billion of current expenditure measures and €1.0 billion of capital expenditure measures.

The biggest current expenditure measure was the graduated 5% to 10% reduction in public sector salaries which was estimated to “lead to savings of over €1 billion in 2010 and in a full year”. These savings are of course in gross pay. Public sector workers were not €1 billion worse off because of the pay cut so the government could not be €1 billion better off because of the pay cut.

The government lost out on the income tax, income levy, health levy and PRSI it would have collected on the pay. The pay of a public sector worker earning €50,000 was reduced to €47,000 as a result of the pay cut (Annex D). The net pay of this worker would have fallen from €33,181 to €31,963. The government might have made a gross pay saving of €3,000 but the employee’s net pay fell by €1,218.

The pay cut might have knocked €1 billion off the gross pay bill but it could not have sucked €1 billion out of the economy. There was also €800 million of cuts announced in the social welfare budget and these are actual cuts to recipients as there is no tax involved. Even with these the level of social welfare transfer payments increased from €20.9 billion in 2009 to €21.0 billion in 2010.

There was about €1 billion of expenditure cuts outside of social welfare but most are small and difficult to evaluate. Yet again, the Capital Budget took a relatively large share of the burden. In 2009 gross voted capital expenditure was €7,329 million; in 2010 it was down to €6,256 million.

And finally we have the €6 billion from Budget 2011. Obviously it will be much harder to see if the targets set for these measures are being delivered upon as it will be another few months before we can know the final year outturns for 2011. The full-year impact of the measures introduced was:

These do indeed sum to €6 billion. However in this instance the “full-year impact” are actually the 2014 impacts rather than the impact that the measure will have in its first full year.

The revenue forecasts for 2011 are going a lot better than in previous years, but by September was still about €400 million below expectations. It is likely that the revenue measures are achieving most of their targets.

On the current expenditure a lot of the cuts were real and reduced the incomes of many. Several others were not quite so ground.

- Social Welfare: A reduced live register from a more intensive labour activation strategy: €100 m

- Health: Demand Led Schemes savings (drug costs and professional fee payments): €390 million

- Health: Other procurement and non-core pay cost savings: €200 million

- Health: Estimated payroll saving from voluntary exit package in HSE: €123 million

- All Departments: Miscellaneous “Administrative efficiencies”: €513 million

These €1,326 million of “measures” account for 60% of the current expenditure measures announced last December. There was €546 million of measures introduced based on the reduction of social welfare payments. At the end of October net current expenditure was €571 million “below profile” it was stated that this was “mainly as a result of the timing of certain payments”.

It will be the year end before we can judge if the expenditure targets were met. In 2010 gross current voted expenditure was €54,265 million. In the Medium Term Fiscal Statement it is forecast to be €53,240 million in 2011 – a reduction of €1 billion.

Once again, the savings on the capital budget are fairly decisive. Gross voted capital expenditure in 2010 was €6,256 million. This year it is estimated to be €4,640 million – a reduction of €1.6 billion.

There are some changes left out of the €21 billion starting total. The February 2009 announcement also included the following:

In addition, the increases provided for under the Review and Transitional Agreement with effect from 1 September 2009 and 1 June 2010 will not now be paid on those dates. Further discussions in relation to these increases will be held in 2011, without prior commitment. This will save a total of €1 billion 2010.

Of course this is just deciding not to spend money that wasn’t been spent in the first place. The Pre-Budget Outlook published prior a month before Budget 2010 included €750 million of cuts to the capital budget. The €961 million of capital cuts announced in the Budget were on top of that.

So how much money has actually been sucked out of the economy? The €21 billion figure is based on an estimate of full-year effects of the measures made at the time the measures were introduced. The Department of Finance forecasts did not perform well, particularly early in the crisis and especially on the taxation side.

For example, the figures from Budget 2009 led to a forecast total tax revenue of €42,780 billion. Tax revenue in 2009 was €33,043 million. The forecast error is almost 25%. It is wrong that we should be sticking to the €21 billion “austerity” total cost when it is clear that this is not what has actually happened.

Looking back over the six packages of cuts and tax increases introduced up to now we can summarise them as follows:

As a result of the half a billion of social welfare measures introduced in October 2008 the total is actually closer to €20 billion rather than the €21 billion figure commonly used. Of course it would be better if the actual impact of these measures than the incorrect projected impact was used.

Let’s look at what has happened to the three areas:

Compared to 2008 voted expenditure is down €4.8 billion (although nearly 90% of this relates to capital expenditure). Over the same period current revenue is down almost €7.4 billion. Although there are other elements to the budget not included here (non-tax revenue, non-voted expenditure) it is hardly surprising the deficit is higher now than it was in 2008, though it has been falling since 2009 (excluding the bank payments).

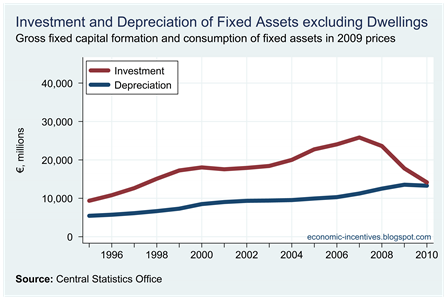

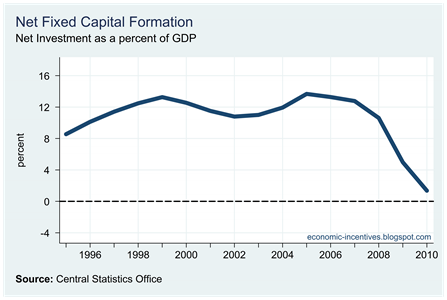

Capital expenditure has fallen €4.3 billion over the period even though €3.5 billion of cuts are in the austerity total. The gap is explained by the November 2009 €0.8 billion of capital cuts that is not included. Capital expenditure is bearing the brunt of the cuts so far. As this is mainly the cancellation of projects that hadn’t even begun the victims of capital cuts are unknown even to themselves.

Almost €9 billion of current expenditure cuts have been announced but gross voted current expenditure is only €0.5 billion lower than it was four years. There has been substantial shifts within that total. At an individual level public sector pay has been cut and many social welfare payments have been reduced. These are real cuts to the individuals and households. However, at the aggregate level current expenditure is largely where it was four years ago.

Almost €8 billion of revenue raising measures have been introduced over the period, but revenue is actually €7.4 billion less than it was four years ago. Once reason for this are the large over-estimates of the impact of the measures by as much as 25% in some cases.

How much austerity have we actually endured? That is not a question that can be answered in a simple analysis such as this. If it was €20.8 billion then that would be a average of €4,500 for every man, woman and child in the country or an average of €18,000 per family of four. There have been tax increases and expenditure cuts but nothing on a scale like that.

I would guess that given the woolly nature of some of the current expenditure measures, the huge overestimates of the impact of the revenue measures, and the actual cuts in the capital budget the last three years has been around €12 billion “sucked out of the economy” with nearly 40% of that as a result of capital expenditure cuts. This is only a guess. It would be useful if the actual figure was produced.