In his Hubert Butler Lecture delivered in St. Canice’s Cathedral, Kilkenny on Saturday 6th August as part of the Kilkenny Arts Festival, Professor Morgan Kelly made reference to 10,000 interest-only mortgages of between €1-2 million.

Here is the actual quote (which is from about 31:35 in the audio file posted here)

“What worries me increasingly are mortgages, and in particular there is a group of mortgages given out - interest only mortgages - that were given out to professionals; to lawyers, solicitors, estate agents, at the peak of the bubble. And about 10,000 of these were given out, and this seems trivial, there are three quarters of a million mortgages out there, why should we care about 10,000 of them? However, it turns out that these mortgages were for properties of €1-2 million each. So these guys would put up like 20% of the price, so 10,000 of these loans of €1.1 million each, which means that there’s like €11 billion in loans to these high-rollers from the boom, most of whom could barely buy you a cup of coffee now.”

Kelly forecasts that that banks would be lucky get back half of €11 billion issued on these loans and predicts a total of €30 billion of additional losses in the banks on top of what has already been accounted for already. Following the huge economic disasters of the last few years this would be the one to push us over the edge, if it comes to pass.

The relatively good news is that there is no evidence that these 10,000 loans of a million plus actually exist. On the other hand there is also no evidence that these 10,000 loans do not exist. They might be out there, or they might not. We just don’t know.

Kelly based his statement on a May 2010 press release from the Irish Brokers Association (IBA) which made reference to this number. I was in contact with the IBA last week and Ciaran Phelan sent an explanatory email. See here.

In the email it is explained that:

As no exact figures are available ( which I believe they should be) we could only estimate the numbers involved which we did using data from Moody's, Central Bank and our own internal conversations with members involved in the mortgage area who have considerable expertise in mortgage lending.

It is very likely that the The Sunday Independent made the same enquiries and received the same email. They carried a front-page story and a longer article that seemed to make a good deal more of the email than might be expected.

There were some misgivings that Morgan Kelly’s claims were based on an article from by Jack Fagan in The Irish Times on the 6th May 2010 (ungated version here). However, when I went searching for a reference to these 10,000 loans, I first came across them in an article by Charlie Weston in The Irish Independent! This article was published on the 30th April 2010, almost a full week before the same details appeared in The Irish Times.

The Sunday Independent article attempted to use Stamp Duty data from the Revenue Commissioners to counter the claim that these 10,000 €million plus mortgages exist. This is inconclusive as the register of transactions included for Stamp Duty is not the full list of all mortgage transactions that occur.

The Stamp Duty numbers show that between 2004 and 2007 around 13,000 stamped transactions took place on properties with prices of more than €635,000. Using this number it is hard to imagine that 10,000 million plus mortgages are in existence.

The problem with using the Stamp Duty data in this manner is that while there was over 50,000 property transactions with Stamp Duty in 2006, there were over 200,000 mortgage transactions. Stamp Duty only covers about a quarter of all mortgage transactions.

In my opinion it is very unlikely that there were 10,000 interest-only mortgages of more than €1 million given to professionals at the peak of the boom. There is no evidence that they exist, but neither is there sufficient evidence to say that they don’t. For the moment let’s assume that they do exist.

Even if these mortgages were issued it is certain that only a fraction, rather than all, of them are in arrears. With the typical tracker-rate mortgage that was available at the time, the annual interest bill on a mortgage of just over €1 million would be around €30,000 or less. Even with the recent downturn this would be a manageable burden from the incomes of most professionals.

Although no figures are available, there is no reason to expect mortgage arrears on these specific loans to be substantially higher than the average for all mortgages. The Financial Regulator reports that nearly 90% of all mortgages are being repaid according to original contract, while 94% have avoided going into arrears of more than 90 days.

If we take it that these 10,000 mortgages are a special case and assume that 25% will default. The banks will be have to write-down a loan of around €1.1 million but will take ownership of the house, which with a 60% price drop, would be worth around half a million. In this very adverse scenario there is likely to be a loss of around €1.25 billion.

It is also important to realise that there is no certainty that all of these loans, such that they exist, were issued by the “covered” banks, most of which have now been nationalised.

Although not proven by the Stamp Duty statistics, it is likely that the actual number of million plus mortgages is lower than the 10,000 figure used by Kelly. Looking at the aggregate mortgage data it could be less than half of this figure. This is as much of a guess as the original estimate provided by the Irish Brokers Association but guessing seems to be the order of the day. If we apply a more realistic default rate of 10% to this estimate, then the losses for the banks will be around €300 million.

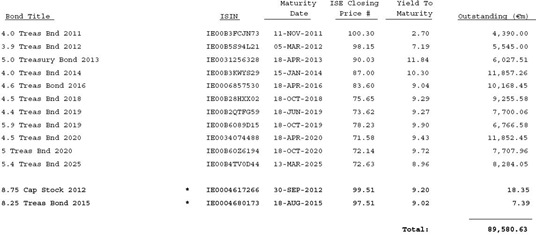

This is nearly 20 times lower than the €5.5 billion if there were to 10,000 defaults and such a loss was more than provided for in the bank stress tests published at the end of March. The banks can handle €300 million of losses on jumbo mortgages. If it comes to it they can handle €1 billion of losses on jumbo mortgages.

It is possible that some of these loans do not appear in the mortgage statistics as they could be structured as commercial loans through a professional’s business. For the present analysis we will stick with mortgages.

The stress tests allowed for €9.5 billion of residential mortgage losses over the next three years. That would probably require something around €16 billion of mortgage defaults.

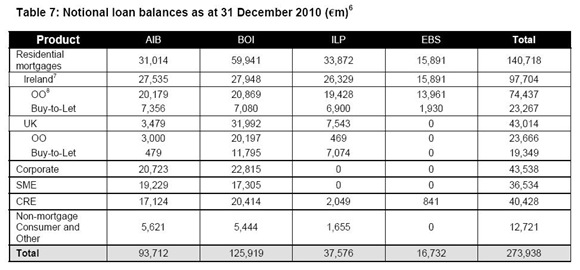

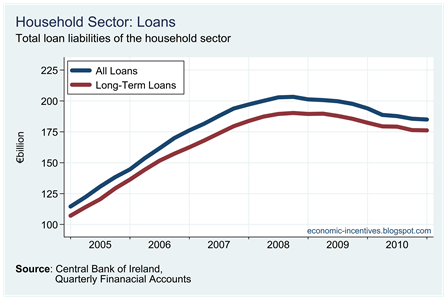

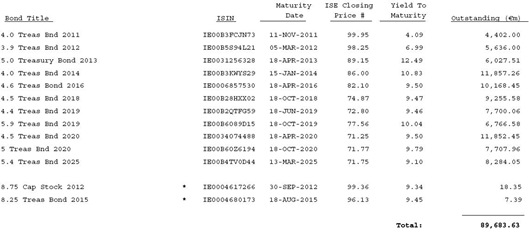

The four main covered banks (AIB, BOI, EBS and PTSB) had €97 billion of residential mortgages at end-2010 (€74 billion in owner-occupied mortgages and €23 billion buy-to-let mortgages). A default rate of 17% over the next three years is allowed for in the stress tests.

If the losses to the covered banks on these 10,000 loans were €1 billion this would be easily absorbed into the €9.5 billion allowed for in the stress tests and there would still be nearly 90% of the loss provision available for the other 90% of mortgages.

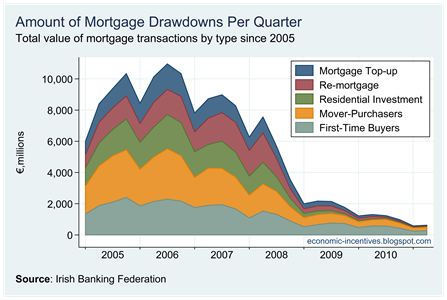

We cannot be sure if these loans exist or not. For the wider economy it would probably be a good thing if they did exist. The Financial Regulator report shows that there was €116 billion outstanding at the end of March 2011 on the 782,000 mortgages covered in its mortgage arrears data. This gives an average mortgage balance of €148,200

If just 10,000 loans account for €11 billion of the total, then the average balance on the remaining 99% is actually €135,900. With 10% of the burden carried by so few people, the average burden across everyone else is much lower. The notion of “average burden” means nothing for someone who has lost their job and is trying to service a €300,000 mortgage but the exercise does give caution when using the aggregate figures.

As for these 10,000 mortgages – it really is hard to know. It will take actual data from the banks to prove or disprove their existence. Even if they are on the books of the banks it is hard to imagine that they will necessitate the banks getting additional capital.

There may be other skeletons remaining on the banks’ balance sheets but this is not one of them. BlackRock Consultants were paid plenty of money to analyse the banks’ loans books so it is unlikely they would have missed these mortgages. This was an interesting anecdote to provide to an audience at an Arts Festival lecture but is by no means another nail in the economy’s coffin.