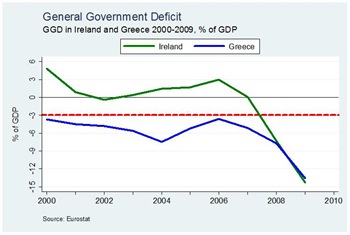

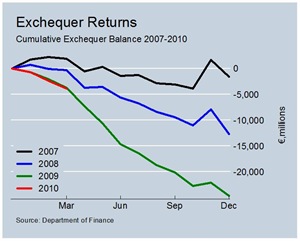

A recent comparison we did here suggested that there was not much difference between the current borrowing positions of Ireland and Greece, except that Ireland is coming from a much lower borrowing base.

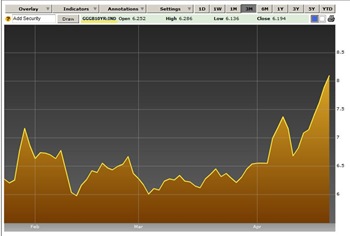

Today’s monthly ECB meeting is set to be overshadowed by the Greek debt crisis which say Greek bond yields reach a record high for the euro period. Here is a graph from Bloomberg of Irish, Greek and German 10-year yields for the past three years. Larger graph here.

[If you click the graph you will get through to the Bloomberg app that allows you to create graphs like the above. The codes for the 10-year bond yields are <GIGB10YR:IND> for Ireland, <GDBR10:IND> for Germany and <GGGB10YR:IND> for Greece. Paste the code between the < > to “add security”. Note that the date line on the horizontal axis is not correct and that when you have more than one variable the vertical axis will measure the relative change in basis points (bps) (one bp = 0.01%).]

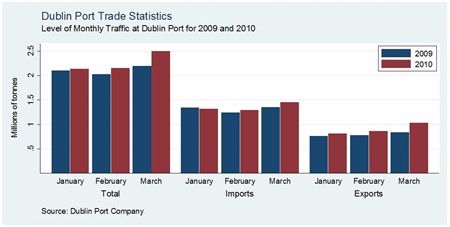

The graph here shows the relative performance of the yields on Irish (green line), Greek (yellow line) and German (orange line) bonds for the past three years, i.e. they are all set equal at the start of the period – 9th April 207. This is actually quite close to reality as back in April 2007 the spread between Irish and Greek bonds versus German bunds was small at just over 0.2%. These figures are in the following table along with the most figures for April 2010 (11.30am today) from Bloomberg.

| | 9th April 2007 10-

Year Yield | Premium over Germany | 8th April 2010 10- Year Yield | Premium over Germany |

| Germany | 4.128% | - | 3.092% | - |

| Ireland | 4.331% | 0.203% | 4.452% | 1.360% |

| Greece | 4.343% | 0.215% | 7.501% | 4.409% |

We see that the premium on Greek bonds has soared to nearly 4.5%. This will have been driven by a drop in the price of the bonds as doubts about Greece’s ability to repay increase. Irish bonds had a higher yield than Greek bonds up to about six months, but as concerns about Greece began to gather momentum Greek yields have soared in the past six months. This difference is even more profound in a graph of the relative performances of tw0-year bond yields. The last six months are crazy and today is the worst yet!

What about Ireland?

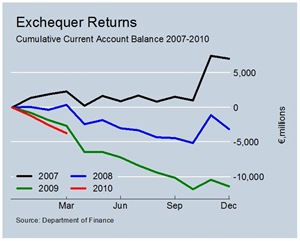

On the other hand, Irish yields have been relatively stable over the past six months with little reaction one way or the other to last December’s budget and the recent NAMA and banking announcements. Irish yields have dropped from their peaks caused by the Deposit Guarantee Scheme (Sep 2008 to 6.025%) and the Anglo Irish Bank Nationalisation (Jan 2009 to 5.872%). After that there was a fall back to under 5% and there has been little volatility in Irish yields since then.

Although yields are set by the market through the buying and selling bonds they are the key determinant of the coupon to be set on new bonds or borrowings. If a country issues a 10-year bond at a 5% coupon, the interest they have to pay on that bond will be 5% for the 10 year duration of the bond. The yield will change as the price people pay to buy these bonds on bond markets change. However, if the country needs to issue new debt, the coupon on these new bonds will have to be close to the yield on existing bonds if the country is going to find people to take them.

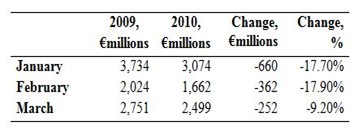

This is the problem Greece finds itself in. Greece needs to borrow or refinance over €50 billion this year with over €11 billion needed in May alone. Doing this at rates over 7% will exacerbate the existing problem. That is if they can find takers for the new bonds. If they can’t, an EU or IMF bailout of some kind is a certainty and even a default becomes ever more likely.

Looking at Ireland it can be argued that we have been performing relatively well (relative to Greece) in the eyes of bond markets. The National Treasury Management Agency seem to think so in the press release to mark their third bond issue of 2010. The Irish 10-year bond was sold at a rate of 4.5%. This is the interest we are committed to paying over the 10 year life of the bond. Even if Irish yields were to soar (because the price of Irish bonds falls) we would not be faced with any additional costs on this debt.

As with Greece, the problem will be with new and refinanced debt. The NTMA are halfway to their €20 billion target for the year. The stability in yields suggest that if they use 10-year bonds they should be able to raise the remainder at a rate close to the 4.5% of the last bond issue. Funding the Exchequer deficits we will have over the next five years should also be possible. Again it could be argued that we are different to Greece.

But with Ireland it is important to look beyond the ‘headline’ figures and look at our ‘off-balance sheet operations’. This of course means NAMA.

NAMA is being financed with Government bonds. We are not giving the banks cash for their development loans but are issuing them with Government Backed Securities. These are different to most government bonds as they have what has been described as a ‘floating interest rate’. The mechanics of how this interest rate will be determined are vague at best as it does not appear to be a market rate.

Unlike most bonds it seems that it is not the purchaser/holder of the bonds who is carrying the risk. If there is an increase in yield (fall in price) of a bond I hold, I suffer the loss. However, the NAMA bonds are being used to support our ailing banks. If the value of these bonds falls, the value of bonds on the bank’s balance sheet falls (assuming they haven’t sold them on) and the recapitalisation process falls short. The NAMA bonds are also short-term bonds meaning they will have be re-issued a number of times during NAMA’s lifetime.

If the NAMA bonds had been issued as long-term (10 year) fixed-coupon bonds then it would be bondholders who carry the risk of these bonds falling in value. In the first instance this would be the banks. However as they are short-term floating-interest bonds it is the taxpayer who carries the risk of these bonds falling in value. If this happens, the bonds will have to be re-issued at a higher rate increasing the cost to the taxpayer, exacerbating an already critical debt situation. Sound familiar?