The previous post on EU corporation tax revenues reminded me of an article for The Irish Times that was published in the Friday business section about a month ago. I don’t think it was available online and was based on this post. Here is a scan of the piece and the text is reproduced below.

Increasing headline rate of corporation tax will do little to unravel ‘Double Irish’

Ireland's headline rate of corporation tax is 12.5% despite some pressure to increase it. Such pressure seems to have been successful in getting Cyprus to increase its corporate tax rate as part of its EU/IMF programme and now only Bulgaria has a lower corporate tax rate in the EU than Ireland.

However, it is not necessarily the headline rate but the calculation of the tax base that is the most important feature of the Irish corporate tax regime.

Recent data published by the Revenue Commissioners show that, in 2010, companies in Ireland reported an aggregate gross profit of just over €70 billion. On these profits, companies paid €4.2 billion which gives an average effective tax rate of 6%.

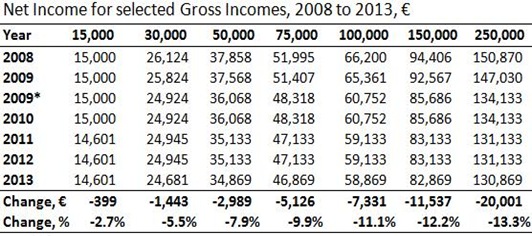

Effective tax rates will always differ from headline tax rates. For example, the headline rates of personal income tax in Ireland are 20% and 41% but the average effective income tax rate for the €78 billion of personal income reported in 2010 was less than 13%.

Personal tax credits are the primary reason for lower effective rate for personal income, though some allowances such as pension contributions mean that taxable income is not the same as gross income.

The difference between gross income and taxable income is also true for companies but to a much greater extent. While gross company profits in 2010 were €70 billion deductions and allowable charges meant that taxable profit was €40 billion.

These deductions include a provision for past losses as only cumulative positive profits are subject to tax. Many companies made significant losses in years prior to 2010 and €4 billion of such losses were used to offset gross profits earned in 2010 for tax purposes.

Companies can also spread the charge for capital expenditure against their gross profit over a number of years. Although capital expenditure, for example on new plant or equipment, occurs at the time of purchase, the allowance for such capital expenditure against company income is spread over a number of years to better match the income flows from the capital item purchased. In 2010, companies in Ireland used €12 billion of capital allowances.

The third major deduction from gross profit are trade charges. These are expenses that companies incur but which are not deducted when the gross profit calculation is made. The most significant trade charge incurred by companies in Ireland is in relation to patent licenses and royalties.

The corporate tax treatment of payments for intellectual property is what makes Ireland an attractive location for computer services companies such as Google, Microsoft and Facebook as well as large pharmaceuticals. Companies incurred around these €12 billion of allowable trade charges in 2010.

Finally group relief for intra-company transfers meant that a total of €30 billion of deductions were made from gross profit to determine the amount of taxable profit.Applying the 12.5% rate to €40 billion of taxable profit meant that the tax payable was around €5 billion. A number of tax credits such as incentives for research and development expenditure in Ireland as well relief to prevent the double taxation of income meant that the total tax paid was €4.2 billion.

The data from Revenue Commissioners also show that the effective rate declines with company income. Companies reporting a net trading income of between €50,000 and €100,000 faced an effective tax rate of 10%. This declined with income and companies with a net trading income of €10 million or more had an effective tax rate of 6%.

This suggests it is the larger companies which are using the reliefs and charges to reduce their tax bill.

Google Ireland has around €12 billion of revenue in Ireland but it makes a much smaller annual profit of around €100 million. Changing the Irish tax rate would generate more tax from the €100 million but would do very little to the €12 billion of revenue flows.

Through a process known as the Double-Irish the profits made by Google Ireland on its €12 billion revenue accrue to a company resident in Bermuda.

It is features of the Irish and Dutch systems and, most importantly, a tax treaty between them that allows the money to be transferred without a tax liability to Bermuda. The profits are taxed in Bermuda where the corporation tax rate is zero.Changing the Irish tax corporate tax rate will not change the effectiveness of this scheme in reducing global corporate tax bills. If we change our business-friendly environment the income flows, and more important the associated jobs, will simply move to another country.