NAMA has begun the process of buying toxic debt from our ailing financial institutions. The first tranche sees €16 billion in loans being bought for a price of €8.3 billion – a ‘haircut’ of 47%. This €8.3 billion is being borrowed to finance these purchases. In essence, public debt is being created to buy private debt which may or may not be paid back.

Three years ago the amount of money being borrowed by Johnny Ronan, Liam Carroll, Bernard McNamara and their ilk had no effect on the ‘man on the street’. With NAMA buying the loans issued to these developers with public debt it is not only Johnny Ronan who is taking a kick in the groin.

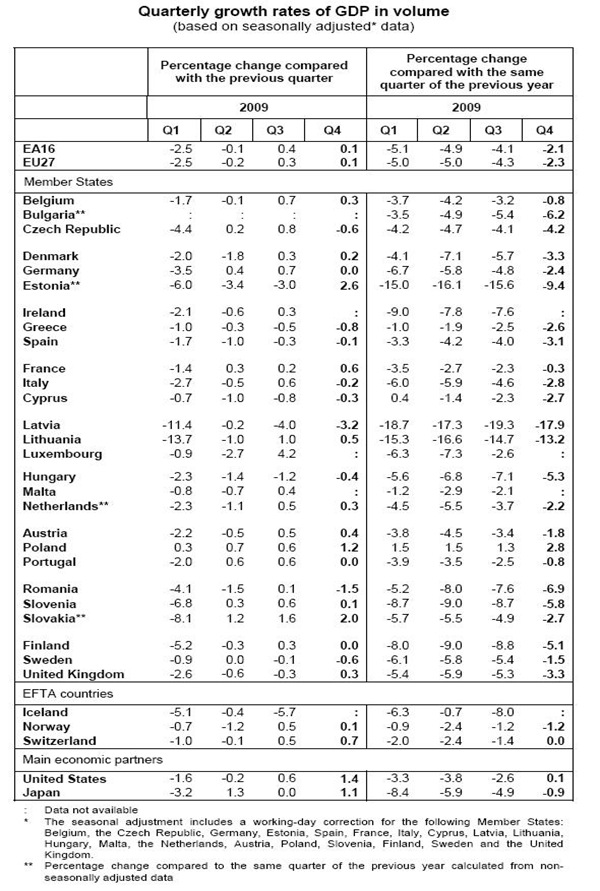

At the end of 2009, Ireland’s general government debt stood at €106 billion. In 2009 the total amount of economic activity in Ireland was valued by the Central Statistics Office at €163.5 billion. Using this Gross Domestic Product (GDP) figure means that Ireland has a debt to GDP ratio of 64.5%.

For households this figure may appear to be a very low debt figure. Consider a household with a net income of €40,000 and an outstanding mortgage of €200,000. This household has a debt to income ratio of 500% and this would be normal for many families. If the state has a debt ratio that is eight times less surely this should not be a problem.

If the household was to devote all of their income to paying off the mortgage it would take five years before the balance would be cleared (assuming zero interest). In order to clear the National Debt of €106 billion, Ireland would have to devote the value of all economic activity to paying off the debt for just under eight months. What takes a family five years could take the country eight months. There are two reasons that make this comparison false.

Firstly, while a family make have access to their entire income to spend as they wish the government can only spend that part of national income they collect in taxes. In 2009 the Irish Exchequer collected €33 billion in tax revenue. With this amount available it would take three years and two months to pay off the National Debt if we poured every euro of tax revenue into it (again assuming zero interest).

Second, the average household will borrow a large amount of money once and then proceed to pay it off over the following years. Therefore a young family might start off with a huge debt ratio and this will reduce over time as the family hopefully pay the debt back. The parents in the family would like to bequeath a house to their children rather than leave them the legacy of a huge debt. Governments tend to borrow, keep borrowing and show little inclination to every pay it back.

In 1995 the Irish General Government Debt was €38 billion. Ten years later with some years of unprecedented economic growth the General Government Debt in 2005 was €38 billion. We had not paid back one cent. What family would enjoy ten years of huge earnings and not pay down their debt. Families may try to avoid leaving a huge debt legacy to their children, governments have no problem leaving such a legacy to the future generations. Ten year olds can’t vote.

In 2009 the Irish government ran an Exchequer deficit of €24 billion. In last December’s Budget the Minister for Finance announced that we would be borrowing a further €20 to fund government expenditure in 2010. There is no sign that borrowings over subsequent years will be substantially lower.

The announcements this week will see further huge increases in the National Debt. NAMA will borrow about €45 billion to buy huge amounts of rubbish loans. The realised value of these loans may be substantially less. The State is borrowing another €8.3 billion to plough into the rubbish bank that is Anglo Irish Bank. There could be another €10 billion put into this black hole.

There are plenty of families around the country who have substantial amounts of debt. But that likelihood is that over the coming years they will pay this off and be debt free by retirement. The Irish state is in huge debt but the problem is that we are showing no indication of paying it back and in fact are likely to add huge amounts to it over the coming years.

Greece is the problem child of the Eurozone and they have a debt ratio of around 115%. By the end of 2010 Ireland is predicted to have an ‘official’ debt ratio of 78%. And that is only because we have convinced to EU to allow us to keep the NAMA borrowings and the further Anglo recapitalisation funds ‘off balance sheet’. Our true borrowings are much closer to Greece.

Brian Lenihan finished his statement to the Dail saying ‘others believe in us, we must believe in ourselves.’ He finished his budget speech last December saying that “we have turned the corner”. It is very clear that was not true. A quick analysis of the true debt figures from Ireland will mean that others will not believe in us for much longer.