The release last week of the Central Bank’s Money and Banking Statistics allows us to update an infrequent analysis of credit card statistics in Ireland.

The headline figure of total credit debt was 6.3% lower in December 2010 than at the same point of 2009. *

* As we will see below there is an anomaly in the December 2010 data which may affect the accelerated rate of decline seen in December. Somebody may be able to offer an explanation. See next *.

[UPDATE: I have an explanation! See bottom of post]

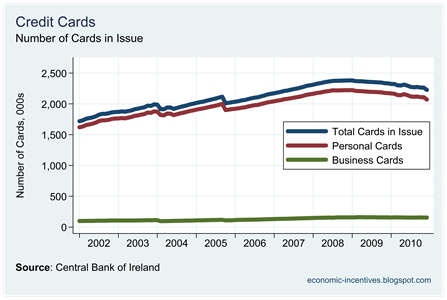

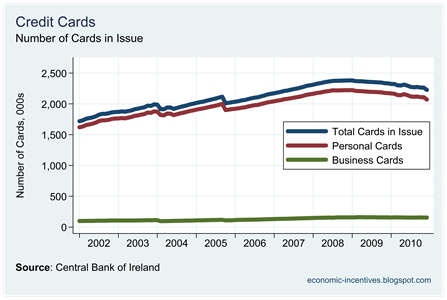

Total credit card debt has not shown any significant annual increase since the start of 2009, but it was in the latter half of 2010 that it actually began to fall. The total number of credit card in issue peaked in January 2009 at 2.38 million. Since then it has fallen and stood at 2.23 million in December 2010.

Nearly 93% of credit cards issued are personal cards and all the fall of 150,000 has occurred here. There are 156,000 business credit cards in issue in December 2010, only slightly down on the 158,000 that were in issue in December 2008. Here are the monthly changes in the number of personal credit cards in issue since January 2007. The largest monthly drop of 36,0000 occurred in the month just past. We cannot tell what proportion of these are cancelled by the consumer or written down by the lender.

We will now looking in more detail at the actual amount of debt on these credit cards, and two of the key drivers of this statistic, monthly credit card purchases and monthly credit card repayments.

The total balance outstanding on credit cards in December was €2.9 billion, which is pretty much the level it stood at back in January 2008. After sustained growth from 2002 to 2007, our total credit card debt has been largely stable over the past three years.

When we look at the monthly activities on credit cards we see that these have been trending down in recent years. In 2010, the average monthly spend on credit card was €939 million. Back in 2007, the equivalent figure was €1,047 million. Our credit card balances mightn’t be coming down (until recently) but there has been a reduction in spending on credit cards. This means that the ratio of outstanding debt to new expenditure has been getting larger and has increased from an average of 2.5 five years ago to 3.5 now.

This graph isolates the monthly new spending and repayments from the graph above that also included total debt. The drop in monthly credit card activity is clearly evident.

The two lines overlap extensively, but it is interesting to note that the quartic trend line for repayments has been above the trend line for new spending since the end of 2007. We will return to this anon but here is the annual change in new monthly spending.

The most severe drops were recorded in 2009, but there was no month in 2010 when spending exceeded the equivalent amount from a year before. Last month new spending on personal credit cards was €824 million. Twelve months previously it had been €929 million, while in December 2007 it was €1,136 million (which was to be its zenith). The fall over that three year period is 27.4%.

If we return to the monthly spending and repayment lines but isolate them for the past three years.

For 29 of the past 36 months repayments on credit cards have exceeded new spending on personal cards. Here is the gap between spending and repayments back to 2002

In the last three years total repayments on credit cards have exceeded total new spending by €1,091 million. Over the same period, as we saw above, the aggregate balances on credits cards have declined from €2,938 million to €2,911 million – a fall of only €27 million. So what happened to the other €1billion and change?

The reason for this difference is because spending and payments alone do not account for credit card balances - the extra amount is accumulated interest (and other charges).

The Central Bank do not give data on the amount of interest added to credit card balances but we can infer it given that the monthly change is approximately new spending plus interest added minus monthly repayment. The change may also be the result of some non-interest charges and duties. Looking at the approximate monthly interest payments and charges since 2005. *

*This graph also shows the anomaly with the December 2010 numbers. The numbers suggest that interest and charges added to balances during the month were negative (-€48 million). Per the data, there was €963 million of new spending on credit cards in December. During the month some €939 million of repayments were made, €24 million less than spending. However, that data also say that even though spending was greater than repayments, balances actually fell by €24 million during the month. Is there any way of explaining this? Repayment of interest or other overcharges?

This accounts for the €1 billion that has been ‘repaid’ off credit cards yet the total debt has hardly declined at all. The leaks occur in April of each year when the annual government duty on credit cards is charged which could have brought in about €150 million over the past three years. Since January 2008 €1,011 million has been added to credit card balances through interest and charges and it appears that about €850 million of this is interest.

With balances averaging €3,000 million over the period it is pretty easy to infer that the average interest rate been charged on this money is in the region of 10%. Credit card debt is expensive debt. If we look at the average balance on personal credit cards we that even though repayments have exceeded new spending for most of the past three years the average balance has hardly moved at all.

In January 2008 the average balance on personal credit cards was €1,295. At the end of 2010 the figure was €1,340. As before our conclusion remains the same:

Our credit card balances are increasing not because we are spending more than we are paying (we do the opposite) but because of the interest on outstanding balances. Although we generally pay the equivalent of our monthly spend each month we do not pay down enough to cover the accumulating interest and reduce the outstanding balances.

UPDATE: The reason for the strange patterns seen in the December 2010 figures can be attributed to the departure of Bank of Scotland (Ireland) from the Irish market. Their outstanding products in December were transferred to Bank of Scotland (UK) and no longer appear in the Central Bank’s Credit Card statistics. With this in mind, we will have to be careful about drawing inferences of changes in the credit card market based on the December figures.