Ireland is in the midst of a crisis that should not be under-estimated. However, for some reason there are many people who go to great lengths to overstate it. A piece in yesterday’s Sunday Indpendent contains the following section in relation to Ireland’s status as a “special case”.

Well, Mr Rehn, we've seen a huge rise in deaths by suicides recently in Ireland, many shown to be connected to austerity. Between 2009 and 2011, 1,563 people in the Republic took their own lives, nearly three times as many as died in traffic accidents. Does this make us a special case?

Unemployment (at 14.8 per cent and rising) is considered "increasingly structural in nature" and more than 150,000 people have emigrated in the past three years. Emigration is the only career choice for the majority of our highly educated young people who have no future in their economically destroyed country. Does this make us a special case?

So many mortgages are in trouble that Fitch, the rating agency, believes at least 20 per cent will default sooner rather than later. Reports also suggest that 1.8 million Irish adults have less than €100 at the end of the month after all the bills are paid. Does this make us a special case?

Suicide, unemployment, emigration, household debt and poverty are all very serious problems which deserve serious attention. They do not get it in the above paragraphs. Some reasons for this are explored below the fold.

In The Irish Times last December Prof. Brendan Walsh wrote:

There is a widespread impression that our suicide rate soared during the recession. In fact, the suicide rate (including deaths due to “events of undetermined intent”) peaked in the late 1990s and fell over the first half of the noughties. While the rate rose significantly in 2009, it fell back in 2010 to the level recorded at the turn of the century.

The suicide rate among the highest-risk group – males aged 25-34 – is now one-third lower than it was in the late 1990s.

A couple of weeks later he gave a presentation on Well-being and Economic Conditions in Ireland at a conference on the Irish economy in Croke Park which illustrates the above findings (see slide 5 in particular).

Table IV on page 53 of the CSO’s Report on Vital Statistics for 2010 provides the number of suicides recorded each year since 1980. The 2011 estimate can be seen in Table 2.15 on page 51 of the Vital Statistics Yearly Summary for 2011. The population figures in the following table are taken from Table 6 in the most recent release of the CSO’s Population and Migration Statistics.

The total number of deaths recorded as suicide rose from 1,424 in 2006-2008 to 1,572 in the three years to 2011. However, over a period when the number of suicides rose by around 10%, the overall population grew by 8%. The suicide rate per 100,000 population did increase between the three-year periods but the rise from 10.9% to 11.5% could not be considered “huge”.

The claim that the unemployment rate is 14.8% “and still rising” can be assessed with Table 3 from the Live Register release.

An unemployment rate of 14.8% is unacceptably high, but in October of last year it was 14.5% and in October 2010 it was 14.2%. The rate has risen from 14.2% to 14.8% but over a two-year period. In fact, the current level of 14.8% was actually reached nine months ago in February and the rate has been almost static since then.

There are a number of important caveats with the unemployment rate. One such is the number of people on ‘Activation Programmes’ who are not included in the Live Register totals. A useful table of these is now provided as a annex to the Live Register Release (see page 13).

Over the past year there has been an increase of 5,245 people availing of these programmes. If these schemes were not available and these people were counted as being unemployed it would have added around 0.25 of a percentage point to the unemployment rate. The rate would be 15.1% rather than 14.8%.

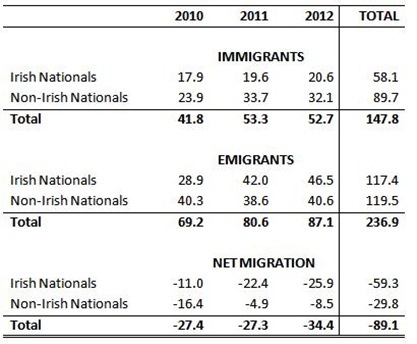

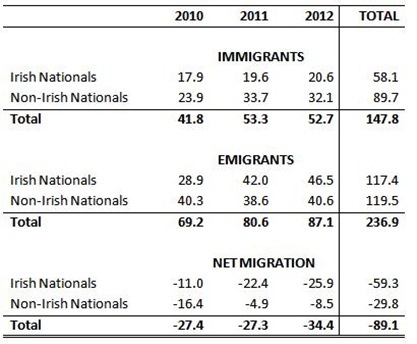

A second caveat is the return to outward migration and this is covered with the claim that “more than 150,000 have emigrated in the past three years”. This table is extracted from the Population and Migration Statistics. (Annual figures are for the 12 months to April in each year.)

Over the past three years far more than 150,000 people have emigrated. The actual figure is close to 240,000. Accounting for the immigration of nearly 150,000 people, the level of net migration is an outflow of nearly 90,000 people, with Irish nationals comprising two-thirds of this total.

This of course further complicates the use of unemployment rates. If the 34,400 net outward migration in the year to 2012 was added to the unemployment numbers it would have added about 1.5 percentage points to the unemployment rate over the year.

It is useful to look at the other side of the coin: the number employed. Here are the overall numbers in employment since 2005.

Getting worse more slowly is still not the same as getting better though. However, hidden with in this total is some detail. Those employed can roughly be broken into three categories:

- Private-sector employees (1,112,000)

- Self-employed (290,000)

- Public-sector (including semi-states) employees (381,000)

Here are graphs that show what has happened to these since 2008. There is a performance difference between the first two and the latter category.

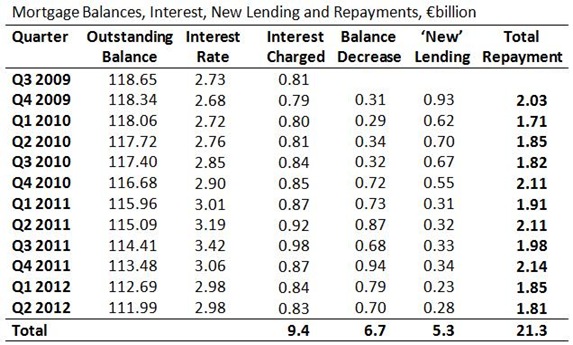

Next is the claim that Fitch “believes at least 20 per cent will default sooner rather than later”. We have previously looked at this in detail. What Fitch actually predicted was a 20% “foreclosure frequency” for residential owner-occupied mortgages in Ireland. In defining “foreclosure frequency” Fitch consider:

“the more than 90 days delinquent performance measure to be most useful for rating assumptions in terms of predicting the borrower’s likelihood of performing.”

Thus, Fitch predicted that 20% of Irish mortgages would fall more than 90 days in arrears. The most recent release from the Financial Regulator show that 10.9% of all mortgage accounts are in arrears of 90 days or more. In the ‘base’ scenario offered by Fitch they have a starting frequency of 10% for the following loans:

- loan is not in arrears;

- full-time employed borrower with full income verification and no adverse credit history;

- amortising loan paying monthly; and

- loan purpose consisting of purchase/refinancing of the primary residence.

With 10% of these loans falling into arrears (and higher frequencies used for loans with poorer characteristics) it is not difficult to see how their overall prediction of 20% 90-day arrears is reached. This could happen and we await further releases from the Financial Regulator to see if the negative trend in the arrears figures is continued.

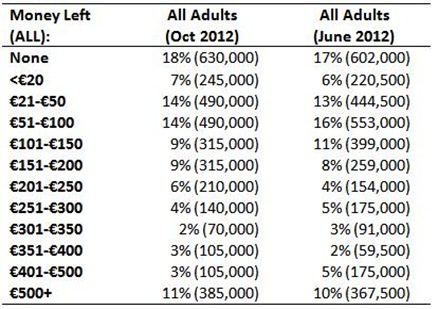

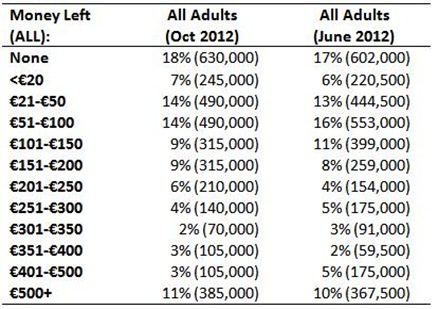

Finally we have the claim that “that 1.8 million Irish adults have less than €100 at the end of the month after all the bills are paid”. This comes from the most recent release of Irish League of Credit Union’s What’s Left survey. The survey was first published in April 2011. The following table is taken from the October 2012 survey.

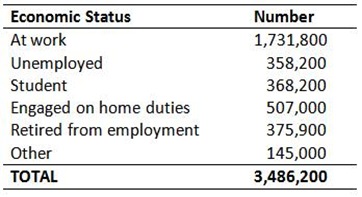

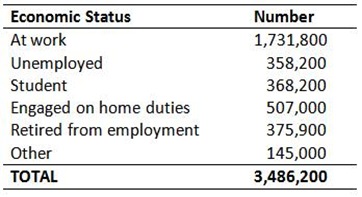

Of course, the ILCU didn’t go around and survey the 3,500,000 people that the above columns total to. They surveyed a sample of 1,000 people which “is nationally representative by Age, Region, Gender and Social Class” and extrapolated from the entire population of people aged 15 and over. Here is a breakdown from the CSO of the population based on self-assessed principal economic status.

This is from Table 10a of the Q2 2012 QNHS, which surveys around 12,000 households and is likely to be a better survey unit of measurement for disposable income. Is it much of a surprise that hundreds of thousands of the people in the above table have less than €100 left after “essential bills” have been paid? Students? Unemployed? Homemakers?

Only around half of the population here is at work and it not clear what “essential bills” actually means in relation to the measure of disposable income referenced in the survey.

The claims that:

- we've seen a huge rise in deaths by suicides recently in Ireland,

- unemployment (at 14.8 per cent and rising) is considered "increasingly structural in nature",

- more than 150,000 people have emigrated in the past three years,

- Fitch, the rating agency, believes at least 20 per cent will default sooner rather than later, and that

- 1.8 million Irish adults have less than €100 at the end of the month after all the bills are paid

may fit a popular narrative but they do not fit reality. Some of them are partially reflective of our reality but some of them are plainly untrue.

The reality is dreadful, truly dreadful but it makes little sense to over-exaggerate it. If such a case was presented to Ollie Rehn, it would quickly be inferred that the only case in which Ireland was “special” was through an inability to use statistics.