Below the fold is a narrative that tries to pull together the revelations in the Anglo tapes this weekend as well as the piecemeal information we already have about the run-up to, and aftermath of, the blanket guarantee introduced in September 2008. For anyone who has shown even a modicum of interest in these developments there is nothing new that follows but maybe it will help to pull a few threads together on the alternatives that were available and the decisions that were taken.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

There were alternatives to the two-year blanket guarantee of almost all the liabilities of six Irish banks that was announced on the morning of Tuesday 30th September 2008.

A little more than 12 hours after its announcement, Prof. Morgan Kelly went on RTE television and accurately foretold that the guarantee would cost the State billions and opined that "there are some non-retail banks that could have been let go and nobody would have missed them".

In a speech delivered three years later the current governor of the Central Bank, Patrick Honohan, said:

“It would have been better had Anglo and INBS been put into resolution as soon as it became clear that their capital was going to be wiped-out by unavoidable losses on developer loans. This should have been evident before September 2008, but was not, leading the Government of the day to include these two failed entities in its blanket guarantee.”

Was Prof. Kelly the only one in September 2008 who knew that Anglo Irish Bank and INBS were bust and should not be saved? While it was evident to Prof. Kelly that their capital would be wiped-out we now know that people in the banks themselves, and also in the Department of Finance, knew this could happen, even if they were not saying so publicly at the time.

The recordings of internal phone calls from Anglo Irish Bank are the most recent source of this information being slowly made public. A lot of attention has been given to the request made by Anglo for €7 billion of liquidity from the Central Bank but what is most telling from the conversation between John Bowe and Peter Fitzpatrick that took place on the 18th of September 2008 is Bowe's prediction of what will happen to the bank.

“I don’t think we’re an easy sell to anybody. So, do I think it’s going to be possible to offload it? No, I don’t. What will it end up being? It could be breaking it up and selling individual books, it could be nationalisation, you know.”

Break-up and nationalisation are outcomes for a bank that is bust. Neither Bowe nor Fitzpatrick put an estimate on the scale of the losses that would lead to these outcomes.

There were loss estimates been discussed in meetings in the Department of Finance. The minutes of some of these meetings have been made available through the Oireachtas Public Accounts Committee. One such meeting is listed as taking place on Thursday 25th September 2008, just five days before the blanket guarantee was announced. At the meeting the then Secretary-General of the Department of Finance, David Doyle is recorded as noting:

“that Government would need a good idea of the potential loss exposures within Anglo and INBS - on some assumptions INBS could be €2 billion after capital and Anglo could be €8.5 billion.”

We know that the public announcements from the government and their officials that, at the time, they were responding to a liquidity crisis but it is clear that, in the background, they knew a solvency crisis was also likely. At this meeting potential losses of €10.5 billion “after capital” of €8 billion were discussed as a possibility.

The two-year blanket guarantee was the eventual outcome but many alternatives were discussed as the crisis reached its zenith. Although the guarantee was introduced it is not clear how much support it had from any source.

We know that in February 2008 a memo prepared by officials in the Department of Finance stated that:

“As a matter of public policy to protect the interests of taxpayers any requirement to provide open-ended/legally binding State guarantees which would expose the Exchequer to the risk of very significant costs are not regarded as part of the toolkit for successful crisis management and resolution.”

This opposition continued in the autumn. When writing about his discussions at the time with the Minister for Finance, Brian Lenihan, columnist David McWilliams said:

“The minister called me the next day and again on Friday, the 19th, when he rang to say they were contemplating a partial guarantee. My view was that such a move would accelerate capital flight, not avert it. From then on, we spoke on a daily basis, but he still wasn't convinced and, from what I could gather, his officials in the department were dead set against a full guarantee, although they didn't seem to be coming up with an alternative.”

At a cost of €7 million, consultants from Merrill Lynch were brought in to come up with a set of alternatives. Prior to their arrival one possibility had already been eliminated - allowing a bank failure. This position was cemented at all official levels through the summer of 2008. In his subsequent report on the crisis, Prof. Patrick Honohan noted that this position “departed from the textbook” but also that it “simplified the decision making process”. This simplification may have cost the State dear.

Taking account of this position Merrill Lynch presented six options in a report provided to the Minister at 6pm on Monday September 29th.

- Immediate Liquidity Provision

- State Protective Custody

- Secured Lending Scheme

- Good Banks/Bad Banks

- Consolidation of Financial Institutions

- Guarantee of Six Primary Regulated Banks

Merrill Lynch did not favour a full guarantee. In fact, in a meeting the previous Friday when they presented their preliminary findings Merrill Lynch warned of the dangers of the guarantee and stated that it “could be a mistake”. In their final report they said:

“The scale of such a guarantee could be over €500bn. This would almost certainly negatively impact the State's sovereign credit rating and could raise issues as to its credibility. The wider market will be aware that Ireland could not afford to cover the full amount if required.”

We know that some of the other options proposed by Merrill Lynch were given some thought. The idea of putting Anglo and INBS into state protective custody using preference shares (a form of nationalisation) was put on the table but the reported reaction of the Taoiseach Brian Cowen was that “we are not f*****g nationalising Anglo”. The consolidation of financial institutions was proposed when Anglo tried to initiate merger discussions with both AIB and Bank of Ireland. Neither was willing to entertain even beginning such discussions.

The tapes released this week show that Anglo’s management were keen to avail of immediate liquidity or secured lending. The €7 billion of liquidity that John Bowe suggested the bank needed could have been provided by the Central Bank. While this would not have stemmed the flow of deposits from Anglo it would have provided the funding for the bank to remain open.

Of course, we know that the €7 billion figure was pretty arbitrary to say the least and was part of a strategy which Bowe described in one of the tapes as:

“The strategy here is - you pull them in, you get them to write a big cheque, and they have to support that money... if they saw the enormity of it up front... they might say the cost to tax payers is too high... if it looks big enough to be important, but not too big that it spoils everything, then I think you have a chance.”

While these has been justified opprobrium to the attitude of Anglo’s management, the reality is that if the €7 billion of liquidity had been provided (or even more than that) the cost to the State of the Anglo disaster might have been significantly less than that incurred as a result of the guarantee actually introduced. The indications are that there are lots more recorded conversations to be released but as of yet there is no evidence that Anglo sought the introduction of the guarantee. In fact, in an interview with IrishCentral.com in November 2011, David Drumm says that Anglo did not look for any guarantee.

“We asked for a certain amount of money to be secured, we were never given an answer. The two weeks, I call it the two weeks of Lehman, because it was that between Lehman and the guarantee being issued, went by with us running around trying to get the Central Bank, the government, we put messages into the Department of Finance because the governor kept telling me ‘you know I am relying on the department of finance here and I have to keep asking them’. He wasn’t getting answers from them. So they were all gone into, I think of it like balls of little mercury, sort of scattered. They just weren’t joined up.

We came to the 30 of September, the 29 of September and we run out of money and I was down at the Central Bank and they said OK you are going to have to ask for emergency funding. Fine how do I do that? They sent me a draft of letter, I got it typed up, I signed it, we need two billion tomorrow to be able to open the doors. So signed that letter and then that was a long day, as you know. I could talk all day about that. We were down at BOI asking them to merge with us. But the end of the day was asking the Central Bank for the emergency funding, two billion. I went home, I ate my dinner and I went to bed and when I woke up in the morning I had several voicemails and messages on my phone and one of them was from Pat Neary to tell me that the government had guaranteed. Then of course I heard it on Morning Ireland. Anglo Irish did not ask them to do that, we asked for a secured loan.”

This is supported by the conversations in the tapes released this week. Anglo was looking for the liquidity to ensure that their doors stayed open.

There were two sources from which this liquidity could have been provided to Anglo. The National Treasury Management Agency could have provided it by converting part of the National Pension Reserve Fund into cash. This was discussed but discounted as it was not part of the remit of the NTMA to support the banking industry.

The second possibility was the provision of a Secured Lending Scheme (SLS) or plain Emergency Liquidity Assistance (ELA) by the Central Bank of Ireland. It is the job of the Central Bank to support the banking industry.

The €7 billion request discussed by John Bowe and subsequent requests by David Drumm were not acceded to. The decision not to provide ELA to Anglo, according to Prof. Honohan, was “open to question” and he further says that while this would not have been ultimately decisive it could have helped buy some time.

“while use of ELA would only have been a temporary solution, it might have bought some breathing space while other possibilities were being explored to address the unprecedented situation that many - not only in Ireland - were facing.”

The provision of this “breathing space” would have cost money but it might not have cost €35 billion that the rescue of Anglo and INBS through the two-year blanket guarantee ultimately cost.

There were alternatives to this guarantee but they were all ruled out for one reason or another. All official levels were opposed to an outright bank failure. Nationalisation was ruled out. Both AIB and Bank of Ireland were opposed to any mergers. Neither the NTMA nor, most crucially, the Central Bank were willing to provide the necessary liquidity to cover the loss of deposits that Anglo was experiencing.

As the alternatives were ruled out the introduction of a guarantee became ever more likely. But even then there were alternatives. The option chosen was a two-year blanket guarantee of almost all the liabilities of the covered institutions. An alternative would have been a partial guarantee of some liabilities. As the problem being address was a deposit flight it was unnecessary to include bonds and other term investments as these were “locked in” – they could not fly out the doors. As Prof. Honohan noted “their inclusion complicated eventual loss allocation and resolution options.” The inclusion of some subordinated debt has close to nothing to support it.

Merrill Lynch also favoured the provision of emergency liquidity to Anglo. Their report concludes that “the extension of a discrete liquidity advance is important to stabilise Anglo (and possibly INBS) and avoid immediate contagion risk.” If this was made available the breathing space provided may have allowed the time for a European response to the fast developing crisis to have evolved.

In fact, at the EU Summit on the 12th of October 2008 it was decided that some form of guarantee was an appropriate response to the banking crisis. The summit statement said:

“To this aim, Governments would make available for an interim period and on appropriate commercial terms, directly or indirectly, a Government guarantee, insurance, or other similar arrangements for new medium term (up to 5 years) bank senior debt issuance. Depending on domestic market conditions in each country, actions could be targeted at some specific and relevant types of debt issuance.”

This was very different to the guarantee introduced in Ireland a fortnight earlier. This proposal was for a guarantee of new bank debt rather than existing debt in the case of the Irish guarantee. This is unlikely to have been extensive enough to stem the tide of deposits from Irish banks, but allied with ECB and Central Bank liquidity it would at least have kept resolution options open. The panic that expanded as September 2008 progressed was partly as a result of the failure of the Central Bank to act as a “lender of last resort”.

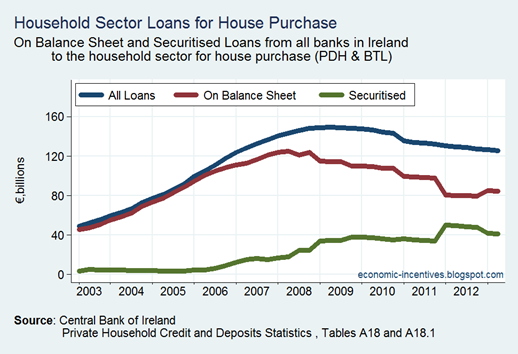

As we now know the blanket guarantee was itself only temporarily effective. It provided an immediate liquidity solution to a long-term solvency problem. The Central Bank was eventually required to provide massive amounts of Emergency Liquidity Assistance to Anglo and Irish Nationwide, while the outflow of deposits that resumed close to the end of the guarantee meant that the reliance of the covered Irish banks on central bank liquidity peaked at over €150 billion – nearly 100% of GDP.

The central bank funding was provided but as a result of the sovereign guarantee almost all of the losses made by the banks in excess of their shareholder equity was covered by the State rather than the banks’ creditors. Close to €25 billion of shareholder equity was eliminated and around €13 billion of losses were subsequently imposed on subordinated bondholders.

So an equally important question to why the guarantee was introduced is why the Central Bank of Ireland did not provide the liquidity assistance that Anglo sought. Maybe we could have saved a billion or ten if Shane Ross’s advice had been followed and Sean Fitzpatrick was made governor of the Central Bank.

Or maybe we wouldn’t. The problem with the guarantee was that it hugely limited the ability of bust banks to be put into resolution. The retail banks (AIB, BOI, EBS & PTSB) were always going to be rescued and the cost of doing so would probably be similar in any scenario with or without a retrospective blanket guarantee.

The key issue is the failure to put Anglo and INBS into resolution and to distribute the cost of covering more of its losses to the banks’ creditors. The failure of Anglo and INBS was always going to cost the State money. At a minimum insured depositors would have to be made good and it is probable that all retail depositors would have been repaid in full. But there were creditors in the bank in September 2008 who could have shouldered some/more of the burden.

There is no doubt that the guarantee was an impediment to this happening but there is also little to indicate that if the “breathing space” that ELA could have provided was available it would have been used effectively. Almost five months after the guarantee was introduced PwC presented a report to the Minister for Finance on the status of Anglo (at a cost of €5 million) and concluded that:

“Under the PwC highest stress scenario, Anglo’s core equity and tier 1 ratios are projected to exceed regulatory minima (Tier 1 – 4%) at 30 September 2010 after taking account of operating profits and stressed impairments.”

This conclusion is incredible given that the previous September there were meetings in the Department of Finance discussing potential losses of €8.5 billion in Anglo “after capital” and phone calls within Anglo itself talking about its possible break-up or nationalisation.

Patrick Honohan is right that Anglo and INBS should have been put into resolution but what is still not clear is how significantly this was prevented by the guarantee. Was the conclusion of PwC taken as fact or was it used as cover for a strategy that had become locked-in because of the guarantee? If the strategy followed was indeed as a result of the guarantee how much did it cost? €5 billion? €10 billion? More?

One things has remained constant in the four-and-a-half years since the guarantee was introduced – there are more questions than answers. Any inquiry into the decision to provide the guarantee must also include a careful analysis of why each of the alternatives available was rejected. We may be waiting a good while yet though.