In 2009 total expenditure by the all the sectors of Irish government was €72 billion. At the same time total receipts of the Irish government were €53 billion. This represents a gap or fiscal deficit of €19 billion. Unlike the costs of our banking collapse, which we hope are once-off, the huge gap in our public finances will continue year after year unless something is done to address it.

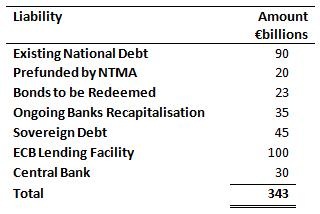

The most pessimistic estimates of the total cost of the bank bailout are for a debt of approximately €70 billion to be assumed by the State. However, if left unchecked, the annual deficit in the State’s own finances would match this amount in less than four years and would quickly run ahead of it. To fund this deficit each we year we have to borrow money from international bond markets, and it is clear that such investors now have growing doubts about our ability to repay this money.

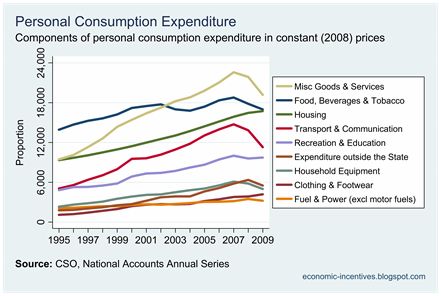

There are two ways which the deficit can be closed: increase revenue or reduce expenditure. Although much of the focus has been on expenditure cuts, the deficit has emerged largely because of a collapse in tax revenue. In 2007, tax receipts for the Exchequer were over €47 billion. This year they will struggle to raise €31 billion. We can attribute the main portion of the deficit to the €16 billion drop in tax revenue, which is largely the result of the evaporation of taxes associated with the now departed construction and property bubble.

So how will we close the gap? It is clear that up to a few weeks ago, the Department of Finance had pinned most of our hopes on increased tax revenue which would be generated by a growing economy that had “turned the corner”. We have a €19 billion budget deficit but the plan to address this presented last December suggested that €7.5 billion in budget ‘adjustments’ would be sufficient to close the gap. The remaining €11.5 billion of the deficit would be covered by the buoyant tax revenue provided when our economy returned to the stellar performance of a few years ago. Well that was the plan anyway.

A few weeks ago the finance spokespeople of main opposition parties trooped into the Department of Finance building on Merrion Street. As the day progressed Joan Burton, Arthur Morgan and Michael Noonan emerged ashen-faced and they were the ones to inform us that the ‘head-in-the-sand’ approach did not have much chance of success. It was Michael Noonan who said that “the adjustment required in the Government's four year budgetary plan will be 'significantly higher' than the €7.5 billion figure previously mentioned”.

Why it took so long for this reality to be grasped by all sides of Leinster House is hard to fathom. The European Commission reviewed our original budgetary plan and concluded that “the budgetary outcomes could be worse mainly due to the programme's favourable macroeconomic outlook after 2010”. This was published by the Commission back in March. Yet, it took until the end of October for this nettle to be finally grasped over here. We cannot expect to fill a €19 billion gap with €7.5 billion worth of changes.

And so, last week the Department of Finance produced outline information on some of elements of the new four-year plan it hopes to publish before the end of the month. These sketchy details informed us that the proposed adjustment between now and 2014 could be of the order of €16 billion. At first glance this appears to be much closer to reality.

Last December, when introducing his 2010 Budget, with €4 billion of adjustments, to the Dail, Minister for Finance, Brian Lenihan said that:

“A Cheann Comhairle, the worst is over. The international economy has exited recession. Recent indicators suggest that economic activity in this country is turning the corner, and my Department is now expecting a return to positive growth within the next six to nine months.

The effort demanded of every citizen in this Budget is substantial, but it is the last big push of this crisis. Further corrections will be needed in the coming years, but none as big as today’s.”

As we now know, the script of the Minister did not reflect the subsequent reality of the Irish economy. The 2011 Budget to be announced in a few weeks will feature €6 billion of adjustments. This will continue with further adjustments of €3-€4 billion in 2012, €3-3½ billion in 2013 and €2-2½ billion in 2014. The upper limit of this total is €16 billion.

The use of the word “adjustment” is akin to the ploy of misdirection used by an illusionist. We think we know what he’s doing, but out of sight the full effect of the trick is being prepared. Adjustment is just a word to hide the reality. Adjustment means expenditure cuts or tax increases, but using the word adjustment avoids specifics so we have no idea how this €16 billion of hardship will be distributed. At the moment it is just a number on a page.

Another key issue is the speed of this process. The €19 billion gap is evident to everyone but what is not so evident is why it has to be closed by 2014. This is an artificial target and one that has been largely self-imposed. When we produced the ‘pie-in-the-sky’ plan last December we said we would have the deficit down by 2014. The EU has taken this as our commitment and has tied us to it. Commissioner Ollie Rehn was here during the week and it is likely he was given further promises that we would cut the deficit by 2014.

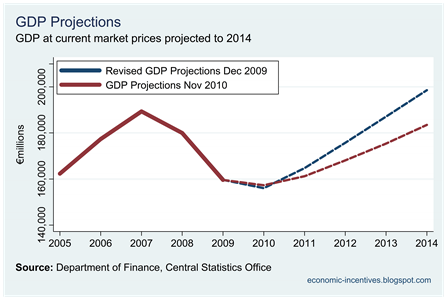

The target we have to reach is a government deficit of less than 3% of Gross Domestic Product by 2014. Whatever the size of the economy is, as measured by GDP, the government have committed to having a deficit of less than 3% of this by 2014. This year we are likely to run a general government deficit of over 12% of GDP which we must reduce to 3% by 2014.

Our target is based on two elements: the size of the deficit and the size of the economy. The four-year plan is aiming for moving goalposts depending how big the deficit is and what happens to the GDP figures. Up to now the hope was that an economy returning to the growth rates of five years ago would help us reach the target by increasing our total GDP.

Last December we were told that the changes required for the 2011 budget would be €3 billion in adjustments. Now that figure is €6 billion and special-interest groups the length and breadth of the country are getting their message out that their funding and services are vital.

Why have we gone from €3 billion to €6 billion and what are we getting for this extra pain? There are three reasons that explain the jump to the €6 billion adjustment: a fall in GDP, a continued widening of the budget deficit, and a more ambitious deficit target for 2011.

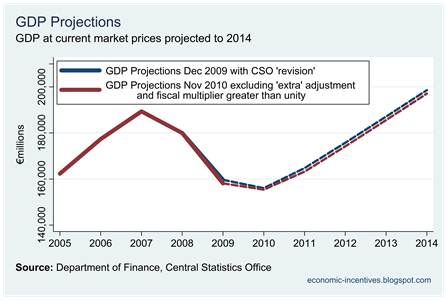

The forecasted GDP number for 2011 has fallen because of a downward revision by the Central Statistics Office of prevision GDP figures. Also, projected GDP for 2011 has fallen because the government has announced they are going to cut more. Direct government expenditure on goods and services (on health and education services etc.) and government funded household expenditure (through social welfare benefits and pensions) are a major component of the economy. If these are cut, the size of the economy is reduced and the allowable budget deficit is reduced. We are cutting more because we have announced we are cutting more. This could be a vicious circle. These changes to the GDP numbers have added €1 billion to the adjustment.

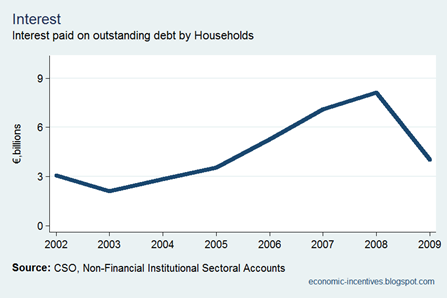

Even with the €4 billion adjustment announced in last December‘s Budget the deficit for this year looks like being even larger than last year. This is because compared to last year, tax revenue is lower, social welfare expenditure is higher and the interest costs on our growing national debt are increasing. We’re trying to close the gap at the same time as the gap is getting wider. This has added a further €1 billion to the adjustment. It is like pouring water into a bucket with a hole in it.

The final reason we have moved to a €6 billion adjustment is the apparent wish to have ourselves viewed as gluttons for punishment. Last year, when we announced the plan to get to a 3% budget deficit by 2014 we said that we would get it down to 10% for 2011, from the 12% this year as an intermediate step on the road to reaching the 3% target. With the economy contracting and the public finances continuing to deteriorate, the Department of Finance has said that we should heap more pain onto the economy by reducing the original target. €1 billion has been added to the adjustment just for the hell of it.

All in all, we will see very little benefit from increasing the budgetary pain from €3 billion to €6 billion. In terms of the EU target we will move from a projected deficit of 10% of GDP for 2011 to a deficit of 9.3% of GDP. We’re going nowhere and it’s like pushing a car with all your might while someone has left the handbrake on.

The government is focusing much of its budgetary efforts on the expenditure cuts and tax increases that it is hoped will meet the 3% target by 2014. We will not meet this target and nor should we be too concerned about this. Yes, the budget deficit has to be addressed, but dancing to a tune called by someone else is not what is required. It is clear that changes have to be made to our public services and our tax system, but they should be done to satisfy the needs of Irish people and not to satisfy an accounting ratio.

We have to decide what is best for Ireland. We have the chance to completely overhaul our public services and tax system but because we are so focussed on an artificial goal we are failing to see the wood from the trees. Making changes at the margin can only offer a temporary solution.

We must decide the kind of public sector and social welfare system we want to have in this country. Do we want a public sector that provides as many services and supports to as many people as possible? If so, we will have to design a tax system that will raise the funds to finance these services. Or do we want to maintain the view of Ireland as a ‘low-tax economy’? If so, we must realise that we will not have the money to provide everything we may wish from our public services. At present we have chosen the impossible. We want the high-cost public services but we cannot pay for them with our current tax base.

Our long-term plan for closing the budget deficit should be based on the type of Ireland we want to see in ten years time. Now is the time to be making these decisions and not fighting over percentage points.