The corporation tax debate goes on – and rightly so. This is a very important issue. It is important for Ireland; it is important globally; and, of course, it is important for the companies.

One of the problems with the domestic debate is that it is almost completely inward focussed. It is pretty obvious that such a dependence on FDI is a significant threat to the domestic economy. Of course, it is also an opportunity if it can be expanded. It may be a misinterpretation but the Chinese word for “crisis” is commonly cited as being a combination of “danger” and “opportunity”.

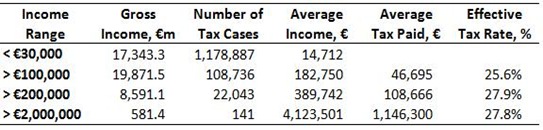

So where are the dangers? The lead story in today’s Irish Times suggests that they are very much domestic in origin and has a set of “effective tax rates” for a group of companies

“including US software company Novell, which paid no tax on Irish profits of $315.6 million in the 16 months to March 2012.”

The company must sell a lot of software infrastructure in Ireland to generate that level of “Irish profits”. Novell also featured in the Irish Times Top 1000 companies recently. The details are here. The figures are notably different. The turnover figure doesn’t even match the profit figure given above.

It is likely that the figures in today’s report are for a Novell company registered in Ireland but one that is not deemed tax resident in Ireland. This distinction is not unusual or unique.

Yesterday, The Guardian ran a significant piece on Apple featuring details on Apple Operations International (AOI) and some links to an Irish employee. AOI featured in the recent Senate report on Apple. The section on AOI is very instructive and is below the fold. If you read it look for indications that this company should be liable for tax in Ireland and compare that to the number of indications that the company should pay tax somewhere else.

Apple Operations International (AOI)

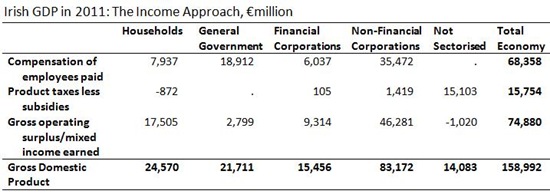

Apple’s first tier offshore affiliate, as indicated in the earlier chart, is Apple Operations International (AOI). Apple Inc. owns 100% of AOI, either directly or indirectly through other controlled foreign corporations. AOI is a holding company that is the ultimate owner of most of Apple’s offshore entities. AOI holds, for example, the shares of key entities at the second tier of the Apple offshore network, including Apple Operations Europe (AOE), Apple Distribution International (ADI), Apple South Asia Pte Ltd. (Apple Singapore), and Apple Retail Europe Holdings, which owns entities that operate Apple’s retail stores throughout Europe. In addition to holding their shares, AOI serves a cash consolidation function for the second-tier entities as well as for most of the rest of Apple’s offshore affiliates, receiving dividends from and making contributions to those affiliates as needed.

AOI was incorporated in Ireland in 1980. Apple told the Subcommittee that it is unable to locate the historical records regarding the business purpose for AOI’s formation, or the purpose for its incorporating in Ireland. While AOI shares the same mailing address as several other Apple affiliates in Cork, Ireland, AOI has no physical presence at that or any other address. Since its inception more than thirty years earlier, AOI has not had any employees. Instead, three individuals serve as AOI’s directors and sole officer, while working for other Apple companies. Those individuals currently consist of two Apple Inc. employees, Gene Levoff and Gary Wipfler, who reside in California and serve as directors on numerous other boards of Apple offshore affiliates, and one ADI employee, Cathy Kearney, who resides in Ireland. Mr. Levoff also serves as AOI’s sole officer, as indicated in the following chart:

AOI’s board meetings have almost always taken place in the United States where the two California board members reside. According to minutes from those board meetings, from May of 2006 through the end of 2012, AOI held 33 board of directors meetings, 32 of which took place in Cupertino, California. AOI’s lone Irish-resident director, Ms. Kearney, participated in just 7 of those meetings, 6 by telephone. For a six-year period lasting from September 2006 to August 2012, Ms. Kearney did not participate in any of the 18 AOI board meetings. AOI board meeting notes are taken by Mr. Levoff, who works in California, and sent to the law offices of AOI’s outside counsel in Ireland, which prepares the formal minutes.

Apple told the Subcommittee that AOI’s assets are managed by employees at an Apple Inc. subsidiary, Braeburn Capital, which is located in Nevada. Apple indicated that the assets themselves are held in bank accounts in New York. Apple also indicated that AOI’s general ledger – its primary accounting record – is maintained at Apple’s U.S. shared service center in Austin, Texas. Apple indicated that no AOI bank accounts or management personnel are located in Ireland.

Because AOI was set up and continues to operate without any employees, the evidence indicates that its activities are almost entirely controlled by Apple Inc. in the United States. In fact, Apple’s tax director, Phillip Bullock, told the Subcommittee that it was his opinion that AOI’s functions were managed and controlled in the United States.

In response to questions, Apple told the Subcommittee that over a four-year period, from 2009 to 2012, AOI received $29.9 billion in dividends from lower-tiered offshore Apple affiliates. According to Apple, AOI’s net income made up 30% of Apple’s total worldwide net profits from 2009-2011, yet Apple also disclosed to the Subcommittee that AOI did not pay any corporate income tax to any national government during that period.

Apple explained that, although AOI has been incorporated in Ireland since 1980, it has not declared a tax residency in Ireland or any other country and so has not paid any corporate income tax to any national government in the past 5 years. Apple has exploited a difference between Irish and U.S. tax residency rules. Ireland uses a management and control test to determine tax residency, while the United States determines tax residency based upon the entity’s place of formation. Apple explained that, although AOI is incorporated in Ireland, it is not tax resident in Ireland, because AOI is neither managed nor controlled in Ireland. Apple also maintained that, because AOI was not incorporated in the United States, AOI is not a U.S. tax resident under U.S. tax law either.

When asked whether AOI was instead managed and controlled in the United States, where the majority of its directors, assets, and records are located, Apple responded that it had not determined the answer to that question. Apple noted in a submission to the Subcommittee: “Since its inception, Apple determined that AOI was not a tax resident of Ireland. Apple made this determination based on the application of the central management and control tests under Irish law.” Further, Apple informed the Subcommittee that it does not believe that “AOI qualifies as a tax resident of any other country under the applicable local laws.”

For more than thirty years, Apple has taken the position that AOI has no tax residency, and AOI has not filed a corporate tax return in the past 5 years. Although the United States generally determines tax residency based upon the place of incorporation, a shell entity incorporated in a foreign tax jurisdiction could be disregarded for U.S. tax purposes if that entity is controlled by its parent to such a degree that the shell entity is nothing more than an instrumentality of its parent. While the IRS and the courts have shown reluctance to apply that test, disregard the corporate form, and attribute the income of one corporation to another, the facts here warrant examination.

AOI is a thirty-year old company that has operated since its inception without a physical presence or its own employees. The evidence shows that AOI is active in just two countries, Ireland and the United States. Since Apple has determined that AOI is not managed or controlled in Ireland, functionally that leaves only the United States as the locus of its management and control. In addition, its management decisions and financial activities appear to be performed almost exclusively by Apple Inc. employees located in the United States for the benefit of Apple Inc. Under those circumstances, an IRS analysis would be appropriate to determine whether AOI functions as an instrumentality of its parent and whether its income should be attributed to that U.S. parent, Apple Inc.

In my view a tax haven is somewhere to put money that provides shelter or cover from tax authorities. Apple is using AOI to shelter huge amounts of money from tax authorities. All the money is in the United States. There is no indication in the report that the money was ever in Ireland. It didn’t even pass through here. It went straight to AOI in the US. On what basis could the Revenue levy a tax a this money that was never here? And yet we’re the tax haven apparently.

[And from September 2006 to August 2012 the Irish director The Guardian attribute a €22 billion annual profit to did not attend any directors’ meeting. Not one.]